In the run-up to Nov. 6, laments about the decline of civility have continued to mount—as seen in headlines such as “A Call for Civility in Days Leading up to the Election,” “Can Civility Be Returned to Politics,” and “Reporter Confronts Obama Over His Lack of Civility.” The latter story, from Fox Nation, cried foul over President Obama’s off-color remark suggesting that Mitt Romney is a serial prevaricator.

We need critiques of incivility, early and often in an election year. And for a particularly thoughtful and earnest one, I recommend James Calvin Davis’s recent essay, “Resisting Politics as Usual: Civility as Christian Witness,” in which he adds a Calvinist punch to such virtues as humility—“an important Christian corollary to the belief that God is God and we are not.”

But we also need critiques of civility itself, or its depth and relevance to questions about justice, truth, and solidarity.

Eric Liu, a former speechwriter and policy adviser to President Clinton, hits a few of the high notes in his Oct. 16 opinion piece in Time, “Civility is Overrated.” He gives civility its due, but says that focusing on it can make us “pay disproportionate attention to the part of politics that’s rational. Which is tiny. Democracy is not just about dialogue and deliberation; it’s also—in fact, primarily—about blood and guts. What we fear, what we love, what we hate, how we belong, this is the stuff of how most people participate in politics, if they participate at all.”

Rational dialogue is just a “tiny” piece of politics? I hope not, but listen to Liu as he draws nearer to the core question of justice.

The danger with pushing for more civility is that it can make politics seem denatured, cut off from why we even have politics. As a Democrat, I want to see more anger, not less, about today’s levels of inequality and self-reinforcing wealth concentration. I want that anger to swell into a new Progressive Era. And as an American, I need to understand better the true sources of anger and fear on the right and the ways those emotions and intuitions yield political beliefs. For all the formulaic shouting in our politics, we don’t often hear the visceral, emotional core of what our fellow citizens on the other side are trying to express.

I highlight here “levels of inequality and self-reinforcing wealth concentration.” Naming that, and doing so with a touch of rage, ought to be part of civil discourse.

Civility is about Caring

The Rev. William Sloane Coffin, one of the greatest preachers of the 20th century, was similarly underwhelmed by the usual pleas for civility. “Personally, I worry more about what’s happening to civil rights than to civil discourse, and I certainly wouldn’t want to talk about civility if all it meant was good manners, manners often at the expense of morality,” he wrote in an essay on civility and multiculturalism that appeared in his 1999 book The Heart is A Little to the Left: Essays on Public Morality.

But, for this liberal Christian stalwart, civility was never about good manners. Look at how civility took on both a theology and an epistemology, a concern for truth, in Coffin’s hands:

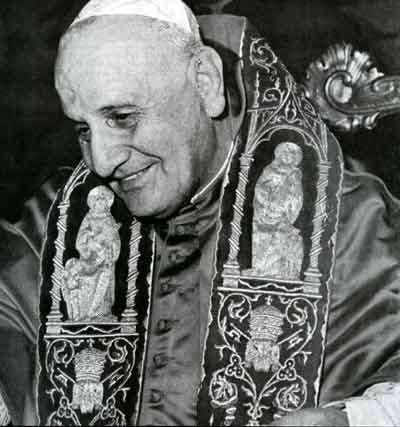

At its most profound, civility has little to do with taste, everything to do with truth. And the truth it affirms, in religious terms, is that everyone, from the pope to the loneliest wino on the planet, is a child of God, equal in dignity, deserving of equal respect. It is a religious truth that we all belong one to another; that’s the way God made us. From a Christian point of view, Christ died to keep us that way, which means that our sin is only and always that we put asunder what God has joined together.

The takeaway? “Caring, I believe, is what civility, profoundly understood, is all about,” Coffin said.

If his essay were less about multiculturalism than about economic justice, he would have undoubtedly emphasized that civility is, above all, about caring for 100 percent of God’s people—but especially for the weakest and most vulnerable among us. How the weak are faring in a society increasingly in the grip of the strong is a fair question for the civility patrol. …read more