On Monday of this week, the police chief of Montgomery, Alabama, formally apologized to Georgia Congressman John Lewis, for what the police did not do in May 1961—protect Lewis and the other young Freedom Riders who arrived at the city’s Greyhound Bus station and were summarily beaten by a white mob. The day before the ceremony (the first time anyone had ever apologized to him for that particular thrashing, the congressman noted), Lewis, Vice President Joe Biden and 5,000 others joined in an annual reenactment of the 50-mile March from Selma, which led to passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. On that occasion 48 years ago, state troopers took a less passive approach and brutalized Lewis and others themselves. A few days before the reenactment, President Obama unveiled a statue of Rosa Parks that will stand permanently in the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall, making her the first African American women to be so honored.

On Monday of this week, the police chief of Montgomery, Alabama, formally apologized to Georgia Congressman John Lewis, for what the police did not do in May 1961—protect Lewis and the other young Freedom Riders who arrived at the city’s Greyhound Bus station and were summarily beaten by a white mob. The day before the ceremony (the first time anyone had ever apologized to him for that particular thrashing, the congressman noted), Lewis, Vice President Joe Biden and 5,000 others joined in an annual reenactment of the 50-mile March from Selma, which led to passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. On that occasion 48 years ago, state troopers took a less passive approach and brutalized Lewis and others themselves. A few days before the reenactment, President Obama unveiled a statue of Rosa Parks that will stand permanently in the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall, making her the first African American women to be so honored.

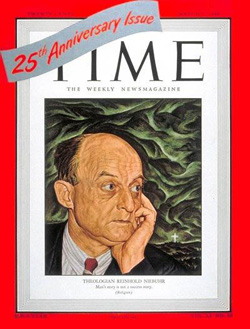

One name that doesn’t figure notably in these various commemorations is that of Lyndon Baines Johnson. But it should. At least that’s my feeling after reading Robert A. Caro’s The Passage of Power, the latest in his magnificent series of Johnson biographies. The writer makes it clear that Johnson wasn’t just a pragmatic politician who acceded to the prophetic demands for action on civil rights. LBJ made it happen, partly out of a visceral identification with the “dispossessed of the earth,” as Caro puts it.

True, there probably wouldn’t have been a Civil Rights Act of 1964 (not that year, anyway) if Parks had lost her nerve on the bus in Montgomery, in 1955, and given up her seat to the white passenger, or if King hadn’t led his nonviolent warriors into the streets of Birmingham in 1963. And the same goes for the Selma marchers and the Voting Rights Act (which the Supreme Court now seems poised to undo). But it’s also true that civil rights legislation was heading nowhere in the administration of the Brothers Kennedy.

JFK and RFK meant well, once they decided to push a bill of that kind. But they didn’t fully grasp what Johnson saw, which is that powerful southern lawmakers would be able to slam the breaks on civil rights, just as they had blocked other liberal domestic reforms ever since the late 1930s. A new strategy was needed to break open the dams of progressive legislation.

Dixie Democrats, in union with sympathetic Republicans, had perfected the art of legislative hostage taking in Congress. They would stall a critical piece of legislation, such as an appropriations bill, or something else that key lawmakers absolutely wanted, until the progressive measure was withdrawn. That’s how they fought off higher minimum wages, expanded unemployment insurance, greater federal aid to education, and other initiatives beginning in the Roosevelt administration (after the early-to-mid-thirties onslaughts of New Deal legislation).

When the Kennedy administration decided to press for a civil rights bill, in June 1963, they sent it up to Capitol Hill along with other must-pass items. Johnson, as vice president, had warned against doing exactly that. He had told Kennedy and his senior aides that they needed to shepherd the other bills through the process, before trotting out civil rights.

Relating a conversation between Johnson and Kennedy confidant Ted Sorensen, Caro writes:

He tried to explain to Sorensen how the Senate works: that when the time came for the vote on cloture [halting a filibuster], you weren’t going to have some of the votes you were promised, because senators who wanted civil rights also wanted—needed, had to have—dams, contracts, public works projects for their states, and those projects required authorization by the different Senate committees involved, and nine of the sixteen committees (and almost all of the important ones) were chaired by southerners or by allies they could count on.

The vice president was ignored as usual—frozen out of the administration’s legislative efforts, partly due to the machinations of RFK, who detested him. The Kennedy people thought they understood legislative realities better than the man who had been “the Master of the Senate,” as Caro dubs him, and they proceeded to play straight into the hands of southern tacticians, who bottled up the civil rights bill. Because of that, Kennedy did not live to see progress on that front.

The general wisdom is that his assassination is what galvanized the country behind his legislative program. And, as shown in The Passage of Power (covering the years 1958-1964), Johnson did move at breakneck speed to capitalize on that momentum. At the same time, he resisted calls to send civil rights to Congress right away, together with other bills deemed necessary—calls issued by Martin Luther King Jr. and the other civil rights heroes. Johnson waited. He kept his eye on the hostage takers, realizing that the best way to thwart them was to not hand them any hostages. He let other bills (appropriations, foreign aid, etc.) pass first. Then he mounted his attack. That’s how civil rights became law in the summer of 1964.

Don’t Leave out Lyndon

Caro points out that many have questioned the sincerity of Johnson’s commitment to civil rights. The author says those people should pay closer attention to words he let out during a meeting with governors at the White House (days after the Kennedy assassination), about why they should fight inequality and injustice: “So that we can say to the Mexican in California or the Negro in Mississippi or the Oriental on the West Coast or the Johnsons in Johnson City that we are going to treat you all equally and fairly.”

Note the “Johnsons in Johnson City,” Texas, where he grew up. Caro analyzes:

He had lumped them all together—Mexicans, Negroes, Orientals and Johnsons—which meant that, in his own heart at least, he was one of them: one of the poor, one of the scorned, one of the dispossessed of the earth, one of the Johnsons in Johnson City. What was the description he had given on other occasions of the work he had done in his boyhood and young manhood? “Nigger work.” Had he earned a fair wage for it? “I always ordered the egg sandwich, and I always wanted the ham and egg.” Nor was it financial factors alone that accounted for his empathy for the poor, for people of color—for the identification he felt with them. Respect was involved, too—respect denied because of prejudice.

Caro continues, relating what President Johnson said as he further reflected on his experiences as a young man teaching impoverished Mexican American children near San Antonio:

He had “swore then and there that if I ever had the power to help those kids I was going to do it.” And now, he was to say, ‘I’ll let you in on a secret. I have the power.” “Well, what the hell’s the presidency for?”

Lyndon Johnson is not known as one of the prophetic personalities of the civil rights era, and shouldn’t be. It was King and others who shaped the vision (in King’s case, of a “beloved community”) and expanded the realm of the possible, which enabled the “Master of the Senate” to work his legislative magic. Still, it’s hard to picture a Civil Rights Act of 1964 or a Voting Rights Act of 1965 without LBJ as well as MLK on history’s stage at that moment. That ought to be recognized more often than it is.

This item was first posted yesterday at Tikkun Daily.