As I write, I’m also packing my toothbrush and notebooks for a conference on Catholic social teaching and climate change, beginning tomorrow at Catholic University in Washington. The climate part needs little explanation, especially after the latest climatic disaster known as Hurricane Sandy. The part about Catholicism or religious faith in general is another matter.

As I write, I’m also packing my toothbrush and notebooks for a conference on Catholic social teaching and climate change, beginning tomorrow at Catholic University in Washington. The climate part needs little explanation, especially after the latest climatic disaster known as Hurricane Sandy. The part about Catholicism or religious faith in general is another matter.

Even TheoPol is not quite prepared to say that theological and moral perspectives are especially critical to discussions of climate change. One would think facts and science—the inconvenient truths, as far as we know them—should be uppermost in the public debate. But theology has a way of crashing parties, including the political ones.

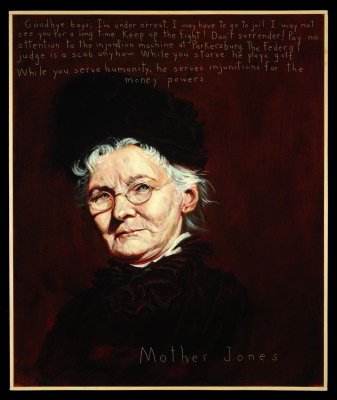

For now, I’ll say there’s an important link between theological ethics and at least one aspect of global climate change: relationships between rich and poor nations. In their 2001 pastoral letter, Global Climate Change: A Plea for Dialogue, Prudence, and the Common Good, the U.S. bishops zeroed in on four points about equity in these relationships.

1) Rich and poor nations alike have a responsibility to address the climate threat;

2) Historically the advanced economies have generated the highest levels of greenhouse gas emissions known to cause climate disruptions;

3) In addition, wealthy nations have a greater capacity to lessen the threat of climate change, while many impoverished nations “live in degrading and desperate situations” that lead them to adopt ecologically harmful practices;

4) Advanced economies should bear the heaviest responsibilities for solutions to climate change. “Developing countries have a right to economic development that can help lift people out of dire poverty,” the bishops noted. “Wealthier industrialized nations have the resources, know-how, and entrepreneurship to produce more efficient cars and cleaner industries,” and they should “share these emerging technologies with the less-developed countries….”

These too are inconvenient truths. Undergirding them are moral and theological principles, among them solidarity and the biblical “preferential option for the poor.” Of course, all this is tendentious drivel if you think global warming is a hoax. Which brings us back to science—until further word. …read more