In the United States, we the people cling to the idea that cherished values such as freedom and opportunity are somehow distinctively American. The accidental philosopher Yogi Berra expressed this sentiment beautifully in the late 1950s when he heard that the mayor of Dublin (as in Ireland, not Ohio) was Jewish. “Only in America!” he declared.

In the United States, we the people cling to the idea that cherished values such as freedom and opportunity are somehow distinctively American. The accidental philosopher Yogi Berra expressed this sentiment beautifully in the late 1950s when he heard that the mayor of Dublin (as in Ireland, not Ohio) was Jewish. “Only in America!” he declared.

In many ways the role that religious faith plays in American politics is exceptional too. Unlike their counterparts in most Western democracies, American presidents continue to routinely invoke the deity in their addresses to the nation. Of course leaders of theocracies do the same, but the U.S. presidential invokers of faith also preside over a government that is religiously neutral. That is a rare juxtaposition.

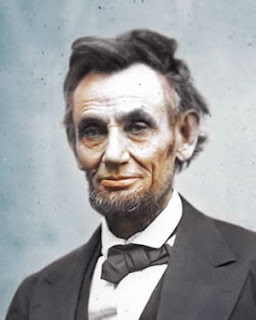

In the American tradition, though, there’s an exception within the exceptionalism on this count. If you look at religiously tinged oratory by presidents at key times in our history, you’ll see that nearly all of them have tried, subtly or unsubtly, to cast their causes in the singular light of divine favor. All except, notably, Abraham Lincoln.

Instead of assuming the God-is-on-our-side posture, Lincoln proclaims in his Second Inaugural Address near the end of the Civil War, “The Almighty has His own purposes.” Instead of presuming to know the whole truth about the crisis at hand, Lincoln lays claim only to the partial truth that “God gives us to see …”

Lincoln is different.

God Talkers in Chief

I recently had occasion to dig through a well-chosen collection of ten major presidential speeches projecting religious themes, courtesy of Boston College’s Boisi Center for Religion and American Public Life and Boston College Magazine (which asked me to report on a student-led “God Talk” seminar sponsored by the center). The Boisi staff, including associate director Erik Owens and doctoral candidate in political science Brenna Strauss, selected the items, which are available here.

One set of those texts relates to the theme of “National Crisis and War” and features oratory by FDR, Reagan, Eisenhower, and George W. Bush in addition to Lincoln.

In one entry, Roosevelt delivers a radio message from the White House to a nation still somewhat unalarmed by the Nazi threat. It’s May 1941, seven months before Pearl Harbor. He warns that the Nazis worship no god other than Hitler and that our freedom of worship is at stake: “What place has religion which preaches the dignity of the human being, of the majesty of the human soul, in a world where moral standards are measured by treachery and bribery and Fifth Columnists? Will our children, too, wander off, goose-stepping in search of new gods?”

Similarly, primal religious emotions are painted on our struggles with foes in other commander-in-chief messages. These include Eisenhower’s First Inaugural Address in 1953 (he sees “the watchfulness of a Divine Providence” over America at the height of the Cold War), Reagan’s 1983 “Evil Empire” speech and Bush’s 2002 State of the Union, which introduced “Axis of Evil” into the lexicon.

Lincoln’s Ineffable God

And then there’s Lincoln, who was born 203 years ago on February 12. He’s the warrior-in-chief against the Confederacy, but there’s no Divine Providence watching preferentially over the Union, in his Second Inaugural (March 4, 1865), which is, as many have described, theologically intense. There’s no casting of political nets around God as Lincoln speaks of North and South:

Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.

Lincoln holds out the possibility that North and South alike might continue to pay, and rightly so, for America’s original sin—slavery.

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

He concludes:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Lincoln’s 703-word Second Inaugural is by far the oldest item in Boisi’s “National Crisis and War” packet, and yet, it’s the most modern in its outlook. Theologically, it is freighted with uncertainty, ambiguity, and a sense of moral tragedy (even our deepest convictions cannot capture the truth), but as he probes the divine nature with soberness and humility, Lincoln arrives at a clear-eyed affirmation of religious faith and American purpose. Yes, Lincoln is different. Lincoln is now. …read more