There’s no doubt that the cultural and ideological fissures in American politics have become more apparent in recent years with the election of Barack Obama, the rise of the Tea Party, and the pushback from Occupy Wall Street. Still, it’s tempting at times to look at our political leaders and say what is often said of academia—that the battles are so vicious because so little is at stake.

The Florida primary showcased a particularly nasty fight between two politicians who have little that separates them in policy substance: Newt Gingrich and Mitt Romney. They resent and resemble each other. For instance, both men supported health insurance mandates before they didn’t. And both of course have serious gripes with Obama (who, incidentally, adopted the originally Republican idea of insurance mandates as part of his healthcare reform package).

When aiming at Obama, the Romney-Gingrich fusillades can seem strangely out of proportion even to their obvious differences with him.

Take Romney’s claim that Obama wants to “turn America into a European-style entitlement society,” while he, Romney, would “ensure that we remain a free and prosperous land of opportunity.” The choice in November, if Romney finally carries the GOP flag, would actually be between two politicians who desperately want to position themselves as “reasonable centrists” in the general election, as John Harwood of the New York Times has pointed out. Put another way, the election would pit a Republican in favor of keeping the Bush tax cuts against a Democrat who would return to Clinton-era tax rates. That adds up to a difference of roughly four percentage points in the top marginal rate. It’s not what separates a socialist strongman from a friend of the free.

Gingrich’s clashes with Obama might be more profound ideologically. But could these possibly justify his assertion that he, Gingrich, honors the U.S. Constitution and the Declaration of Independence while Obama supports neither? As Speaker of the House during the ’90s, Gingrich did more than any other political figure to envenom the public discourse. He helped make it safe for politicians to habitually attack the decency and good faith of their adversaries.

No small amount of that incendiary rhetoric has rubbed off on the left. Many liberals have lapsed into the habit of condemning Republican “lies.” Very often, these alleged prevarications are really just matters of opinion, like the GOP claim that the rich already pay too much in taxes. To call them lies is itself a distortion.

When Things were Rotten

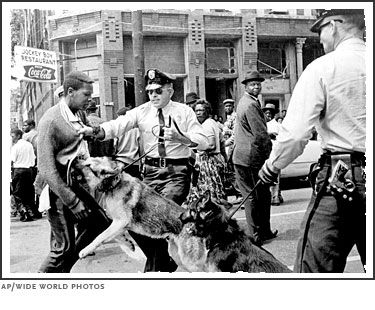

Plainly, there’s a lot to fight over in 2012. But there was far more at stake a half-century ago when Martin Luther King and the civil rights marchers, walkers, and sitters showed another way of relating to the opposition. You might say they had some serious differences with the segregationists. They were living in what was, for African Americans, a state of terror in the Deep South. But they steered a way to mutual understanding even as they took to the streets.

During the movement’s early years, King went to such lengths as to answer his hate mail respectfully—thanking his correspondents for writing, and proceeding to reasonably state his differences with these unreasonable points of view. (There was less time for that as the freedom campaigns intensified and the hate writers became more prolific.) During the few times he lost his cool with a segregationist or, some years later, with a supporter of the Vietnam War, King would reproach himself for hours, as his biographers (including Stephen Oates) have described. And then he’d pick up a phone and apologize.

Unlike today when political dialogue is often clogged with conversation stoppers like “lies” and “dishonesty,” King and his supporters found ways to keep the conversation going. They engaged in rational argument, as King did in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail (in which he asked his white-clergy critics to forgive him “if I have said anything that overstates the truth,” and begged God to forgive him if he had understated the truth). He tried to open channels of discussion because of his belief that hearts could change, but also because, as a trained theologian, he could “see that some truth, however minuscule … may exist in quite opposite ideas and viewpoints,” as the social ethicist Rufus Burrow Jr. has noted.

In other words, everyone has a piece of the truth—not the most likely message of a Super PAC ad.

Yes, King denounced and confronted: history told him that oppressed people seldom gain their freedom by dropping hints. But he and his fellow campaigners made it clear enough that the prize they eyed was not just their own freedom. It was friendship and community with white America, what King often referred to, in rich theological tones, as “the beloved community.”

During this Black History Month, it’s worth recalling how civil rights activists often spoke large-heartedly about people who set off bombs in their churches or tacitly condoned the terror. It shouldn’t be too hard to practice a similar forbearance today with political rivals who would like to raise (or lower) taxes by a few percentage points. …read more