During this past week of JFK commemorations, a number of commentators have pointed out that Kennedy’s thinking on civil rights “evolved” during his three years in office. That’s always a pretty safe way to describe a gradual change in policy, which clearly did happen in the Kennedy administration. But what this explanation misses is that Kennedy, from the start, understood what African Americans were saying about their subjugation in the Deep South—unlike Eisenhower before him. At the same time, Kennedy was also able to compartmentalize the challenge of civil rights, as he was known to do with issues in his private life.

During this past week of JFK commemorations, a number of commentators have pointed out that Kennedy’s thinking on civil rights “evolved” during his three years in office. That’s always a pretty safe way to describe a gradual change in policy, which clearly did happen in the Kennedy administration. But what this explanation misses is that Kennedy, from the start, understood what African Americans were saying about their subjugation in the Deep South—unlike Eisenhower before him. At the same time, Kennedy was also able to compartmentalize the challenge of civil rights, as he was known to do with issues in his private life.

The two-part PBS documentary marking the 50th anniversary of his assassination offered a snapshot of this civil-rights compartmentalization. Kennedy went before Congress in May 1961, shortly after the Freedom Riders boarded their integrated buses, and he said not a word about them and their near-slaughter at the hands of a segregationist mob in Alabama. In that special joint session of Congress, he turned attention to what he saw, at that early moment, as the transcendent cause of his time: the liberal Cold War.

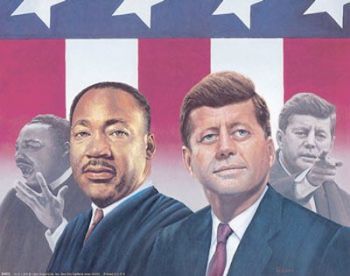

Still, for a white man of power, Kennedy had a rare grasp of African American self-understanding. It was an existential understanding—especially of those black leaders who had run out of patience with puny steps toward civil rights. Kennedy talked about these questions repeatedly with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and even when he was being contrary with King—usually for political or strategic effect—he knew better.

During a June 1963 meeting at the White House, Kennedy was advancing the argument that the civil rights movement should refrain from street protests while the administration negotiated with Congress on a civil rights bill. King was there with four other civil rights leaders; also present were RFK, Lyndon Johnson, and labor chief Walter Reuther.

Kennedy told King—according to a paraphrase by King biographer Stephen B. Oates—that he “understood only too well why the Negro’s patience was at an end.” But the president warned that more high-profile demonstrations would give some wavering members of Congress an excuse to say (in Kennedy’s words, quoted by Oates in Let the Trumpet Sound): “Yes, I’m for the bill, but I’m damned if I will vote for it at the point of a gun.”

Kennedy was arguing specifically against plans for a March on Washington (which materialized two months later). King replied, “It may seem ill-timed. Frankly, I have never engaged in any direct action movement which did not seem ill-timed.” Then King added, invoking the successful demonstrations that spring in Birmingham, Alabama: “Some people thought Birmingham ill-timed.”

At that moment, Kennedy interjected, no doubt with a smile—“Including the attorney general,” RFK. Aside from seizing an opportunity to tease his little brother in the room, John F. Kennedy was acknowledging in his witty way that, yes, “the Negroes” could not wait any longer for their God-given human rights. JFK understood. …read more