Posted today in Tikkun Daily

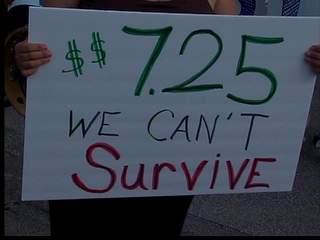

At a time when too many people are out of work and too many others are holding down two or three jobs just to survive, it might seem a bit frivolous to lament the lost art of leisure. But leisure—restorative time—is a basic human need. And fewer people are getting the benefit of it, apparently even when they’re on paid vacations.

A new Harris survey finds that more than half of all U.S. employees planned to work during their summer vacations this year—up six percent from the previous year. (Email is a prime suspect in this crime against leisure.) Soon enough, all of us will be taking presidential-style vacations like the one starting tomorrow. That’s when the Obamas arrive on Martha’s Vineyard, no doubt just in time for the president’s first briefing on national security.

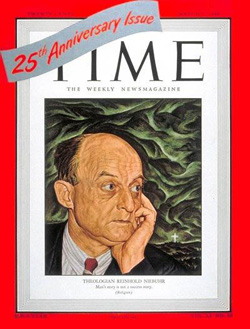

In my mind, no one has gone to the philosophical and theological heart of this matter more tellingly than the German American thinker Josef Pieper in his 1952 classic, Leisure: the Basis of Culture.

“The provision of … leisure is not enough; it can only be fruitful if man himself is capable of leisure,” he wrote. In Pieper’s book, workaholics are not the only ones who might be leisure challenged. Some of the most avid vacationers, with clear goals in mind for their getaways, might also be missing the point.

To understand why, one must appreciate the degree to which leisure is a state of mind, “a condition of the soul,” as Pieper styled it. And part of that soul of leisure is effortlessness. “Man seems to distrust everything that is effortless … he refuses to have anything as a gift,” he explained, resting on St. Thomas Aquinas’s teaching that virtue resides in “the good rather than the difficult.”

Those looking for useful tips on how to get more out of their leisure will not find them in Pieper’s meditations. Leisure is not something we do to “get” anything, in fact. According to him, it is worthwhile in itself, not merely a means toward an end.

Examples of such leisure are beside the point, because it’s not so much the activities as the spirit one brings to them. “Messing about” was how G.K. Chesterton put it. So a Chestertonian leisure activity could be almost anything—say, tennis. But the purpose wouldn’t be to “work on my backhand,” as they say.

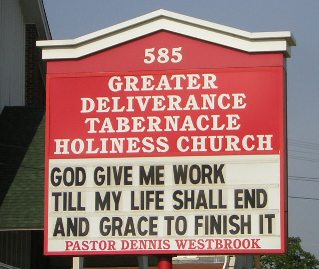

What is the ultimate form of leisure? Pieper’s answer is not what many would give, including those of us who have experienced the unrest of being with fidgety children in a house of prayer. But for Pieper, the very image of leisure is divine worship.

Celebrating God in a holy place is leisure at its most sublime because it’s something we do purely for its own sake (or else it is not divine worship), Pieper taught. He explained that when people are truly at leisure, they are transported beyond the workaday world into another realm. And this is what transpires in the rituals, he submitted: “Man is carried away by it, thrown into ecstasy.” I’d call it a “mystical” realm or simply a “restorative” one before I’d say “ecstatic.”

It’s getting harder to plumb those depths of leisure, even if you’re blessed with paid vacation time (and increasing numbers of Americans are not). Still trickier, it doesn’t really work if you’re trying. …read more