The Rev. William Sloane Coffin, a liberal Protestant stalwart who could spot self-righteousness a mile away—and in himself—recalled visiting his mentor Reinhold Niebuhr in 1966. Niebuhr, who had taught social ethics at Union Theological Seminary in New York, was in poor health and spending his last years at his summer home in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. As Coffin entered the room, the great theologian smiled from his bed and said, “Ah, Bill, I heard a speech of yours the other day on the radio. You reminded me of my youth—all that humor, conscience, and demagoguery.”

The Rev. William Sloane Coffin, a liberal Protestant stalwart who could spot self-righteousness a mile away—and in himself—recalled visiting his mentor Reinhold Niebuhr in 1966. Niebuhr, who had taught social ethics at Union Theological Seminary in New York, was in poor health and spending his last years at his summer home in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. As Coffin entered the room, the great theologian smiled from his bed and said, “Ah, Bill, I heard a speech of yours the other day on the radio. You reminded me of my youth—all that humor, conscience, and demagoguery.”

That visit is recounted in Coffin’s 1977 memoir Once to Every Man. The story came to mind as the youngish bands of Occupy protestors hit the streets earlier in the fall, and again in recent weeks as police broke up their encampments in city after city. What’s next for these dauntless activists who have already introduced a new politics in the United States? What will they do with their anger, passion, and conscience? Might there be a little more humor and a tad less demagoguery?

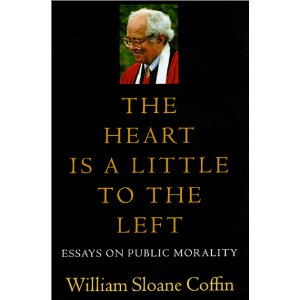

In reflecting on these and other questions, they and the rest of us may find some wisdom in the words of Bill Coffin, who assumed the mantle of leader among left-leaning Protestants after the assassination of his friend, Martin Luther King, and who died in 2006. This year, Dartmouth College Press felicitously reissued Coffin’s 1999 book The Heart is a Little to the Left: Essays on Public Morality. What follows are some nuggets from that slim and veracious volume.

Love and Anger …

• I like St. Augustine’s observation: “Hope has two beautiful daughters. Their names are anger and courage; anger at the way things are, and courage to see that they do not remain the way they are.”

• But in all this talk of anger, there is a caveat to be entered. We have to hate evil, else we’re sentimental. But if we hate evil more than we love the good, we become good haters, and of those the world already has too many. However deep, our anger must always and only measure our love.

• Socrates was mistaken. It’s not the unexamined life that is not worth living; it’s the uncommitted life.

The Bible and Us …

• I read the Bible because the Bible reads me. I see myself reflected in Adam’s excuses, in Saul’s envy of David, in promise-making, promise-breaking Peter.

• [The Bible] is a signpost not a hitching post. It points beyond itself, saying, “Pay attention to God, not me.”

• It is a mistake to look to the Bible to close a discussion; the Bible seeks to open one.

• Christians have to listen to the world as well as to the Word—to science, to history, to what reason and our own experience tell us. We do not honor the higher truth we find in Christ by ignoring truths found elsewhere.

Might and Right …

• True patriots carry on a lover’s quarrel with their country, a reflection of God’s eternal lover’s quarrel with the entire world.

• The United States doesn’t have to lead the world; it has first to join it. Then, with greater humility, it can play a wiser leadership role.

• About the use of force I think we should be ambivalent—the dilemmas are real. All we can say for sure is that while force may be necessary, what is wrong—always wrong—is the desire to use it.

The Spiritual and the Knowable …

• Spirituality means to me living the ordinary life extraordinarily well.

• All of us tend to hold certainty dearer than truth. We want to learn only what we already know; we want to become only what we already are.

• We forget that both the tree of life and the tree of knowledge are deeply rooted in the soil of mystery. The most incomprehensible fact is the fact that we comprehend at all.

I thought you’d mention another instance. One of the things Cardinal Bernardin was shown when he went to Chicago is where he would be buried, beside predecessor John Cody. He smiled and said the place was satisfactory noting his future position with respect to Cody, “I always was a little to the left of John Cody.”