Heschel died a few months later on December 23, 1972. But he lived to see and help usher in what he surely knew was one of the most prophetic moments in American history.

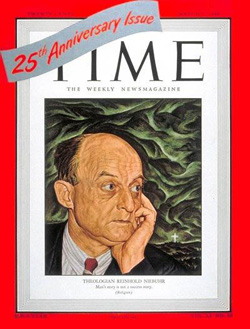

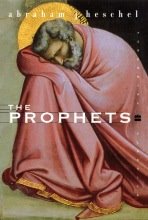

His timeless study, The Prophets, was published in late 1962, and it ushered out the soothing spiritual happy talk of the ‘50s. The Polish-born mystic wrote admiringly that the biblical prophet is “strange, one-sided, an unbearable extremist.” Hypersensitive to social injustice, the prophet reminds us that “few are guilty, but all are responsible,” Heschel declared.

The book was read widely in civil rights circles. In his 1963 “I Have a Dream Speech,” the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. echoed the prophet Amos—“Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a might stream.” King used a translation barely known at the time but common today—Heschel’s translation. The standard rendering had been “judgment” rather than “justice.”

King and Heschel had first met in January of that year at a conference on religion and race, in Chicago, and the two became fast friends. In 1965, they and others locked arms in the first row of the march from Selma to Montgomery—a lasting image of that whole struggle. Afterward, Heschel remarked, “I felt like my legs were praying.”

By then, with his surfeit of white, wavy hair and his conspicuous white beard, Heschel looked as well as sounded the part of an Old Testament prophet. And within a year he was waging prophesy on another front, as co-leader of Clergy Concerned About Vietnam, a collection of kindred spirits emanating from New York City, where Heschel taught at the Jewish Theology Seminary.

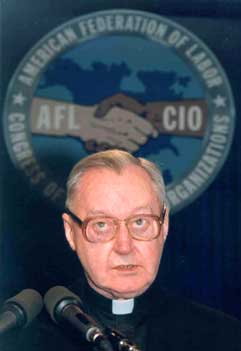

This prophetic club included, among others, the otherworldly Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan and the swashbuckling liberal Protestant minister William Sloane Coffin, and the group persuaded King to ramp up his antiwar activism. Heschel struck the spiritual high notes when he preached at a 1968 mobilization in Washington about “the agony of God in Vietnam.” He declared: “God’s voice is shaking heaven and earth, and man does not hear the faintest sound.”

Devolving Prophecy

In the late ‘60s, young radicals imitated this style of prophetic denunciation; leaders of the secular New Left often spoke self-referentially of a “prophetic minority.” The counter-cultural stance took on a conservative hue in the late ‘70s, with the ascending religious New Right. Fundamentalist leader Jerry Falwell often credited King with his conversion to a political and confrontational faith.

In a way, much of politics today has gone prophetic. The vilification of one’s opponents, the overstatements about a “war on religion” or a “war on women,” the jeremiads against the one percent or the 47 percent, have come to be expected. (Outside of the religious right, it is largely in secular politics that one sees this skewing of prophetic discourse.) Do we really need more prophets uttering their “strange certainties” and speaking “one octave too high,” as Heschel affectionately wrote of the biblical prophets?

The rabbi would say yes, but he’d have in mind a different prophetic style.

He, King, and company usually found a way to join prophecy with civility, denunciation with doubt. This isn’t like walking and chewing gum at the same time. It’s much harder. Heschel said in his old-world way (as related by his biographer, Edward K. Kaplan), “Better to throw oneself alive into a burning furnace than to embarrass a human being in public.” King, in his Letter from Birmingham Jail, pleaded with his white-clergy critics to forgive him “if I have said anything that overstates the truth.”

They did sail over the top at times, as when King, appearing with Heschel at Manhattan’s Riverside Church in 1967, branded America “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” But that’s what prophets do. In their realm, unreasonableness is no vice, particularly when seeking to “strengthen the weak hands,” as the prophet Isaiah said in regard to the lowly and oppressed.

And that was Heschel’s prophetic calling—not so much to take the right stands, but to stand in the right places. …read more