During an eventful appearance at Boston College a while back, Ta-Nehisi Coates told the story of why he wrote the bestseller Between the World and Me. It is a slim volume—a meditation on what it means to be Black in America, framed as a letter to Coates’s 15-year-old son, Samori. Throughout the long evening, his tone was passionate but conversational, with not a whiff of preachiness. “The kind of oppression that black people feel in this country is very, very physical. It’s about people taking possession of your body.”

True to the Story It Needs to Tell

“Selma” the movie made a splash when it first appeared on the big screen, causing ripples of controversy—much of it centering on portrayals of head butting between Martin Luther King and President Lyndon Baines Johnson. So, I was a little surprised when I finally saw the movie, on an MLK Day weekend. As I quickly learned, “Selma” is not essentially about MLK or LBJ. It is, of all things, about Selma.

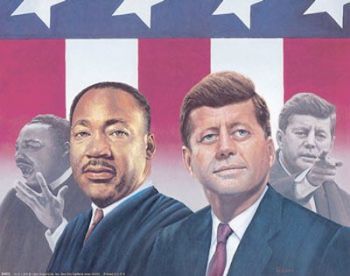

JFK Understood

The two-part PBS documentary marking the 50th anniversary of his assassination offered a snapshot of this civil-rights compartmentalization. Kennedy went before Congress in May 1961, shortly after the Freedom Riders boarded their integrated buses, and he said not a word about them and their near-slaughter at the hands of a segregationist mob in Alabama. In that special joint session of Congress, he turned attention to what he saw, at that early moment, as the transcendent cause of his time: the liberal Cold War.

Still, for a white man of power, Kennedy had a rare grasp of African American self-understanding. It was an existential understanding—especially of those black leaders who had run out of patience with puny steps toward civil rights. Kennedy talked about these questions repeatedly with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and even when he was being contrary with King—usually for political or strategic effect—he knew better.

During a June 1963 meeting at the White House, Kennedy was advancing the argument that the civil rights movement should refrain from street protests while the administration negotiated with Congress on a civil rights bill. King was there with four other civil rights leaders; also present were RFK, Lyndon Johnson, and labor chief Walter Reuther.

Kennedy told King—according to a paraphrase by King biographer Stephen B. Oates—that he “understood only too well why the Negro’s patience was at an end.” But the president warned that more high-profile demonstrations would give some wavering members of Congress an excuse to say (in Kennedy’s words, quoted by Oates in Let the Trumpet Sound): “Yes, I’m for the bill, but I’m damned if I will vote for it at the point of a gun.”

Kennedy was arguing specifically against plans for a March on Washington (which materialized two months later). King replied, “It may seem ill-timed. Frankly, I have never engaged in any direct action movement which did not seem ill-timed.” Then King added, invoking the successful demonstrations that spring in Birmingham, Alabama: “Some people thought Birmingham ill-timed.”

At that moment, Kennedy interjected, no doubt with a smile—“Including the attorney general,” RFK. Aside from seizing an opportunity to tease his little brother in the room, John F. Kennedy was acknowledging in his witty way that, yes, “the Negroes” could not wait any longer for their God-given human rights. JFK understood. …read more

Go Jonny Gomes: Political Gratitude in Play

If I were looking for a nearly perfect expression of social or even political gratitude, I’d have to look no further than Jonny Gomes and his remarks last night after the Red Sox beat the Cardinals 4-2, tying up the World Series. The Sox leftfielder was a last-minute stand-in for Shane Victorino, whose lower-back problems were acting up, and in the top of the sixth, he jumped on a sinkerball that didn’t sink and drove it over the leftfield wall in Busch Stadium. The three-run homer put the Red Sox on top, where they stayed.

Speaking to the press afterward, Gomes—who had a heart attack when he was 22, survived a car accident that killed one of his best friends, and was no stranger to poverty and homelessness while growing up in northern California—had this to say when asked for his thoughts:

What’s going on inside here is pretty special, magical. There’s so many people and so many mentors and so many messages and so many helping paths and helping ways for me to get here, that there’s a lot more than what I could bring individually.

Among the “helping paths” that Gomes was alluding to were those provided by the town and citizens of Petaluma, California, which saw to it that he and his older brother had enough to eat and a place to sleep through many hard times. A visible sign of his gratitude is the “707” stitched into his glove and shoes. It is the area code of Sonoma County, which includes Petaluma.

I realize that Gomes wasn’t trying to score a political point here, but he wasn’t just talking baseball, either. At that news conference, the 32-year-old was delivering what amounts to a countercultural message. The fashion of the day is to preach some variation of the I-did-it-all-by-myself gospel. In contrast, Gomes teaches the a-lot-more-than-what-I-could-bring-individually ethic.

And who are the did it it all by myselfers? In our time, they are often the ones who have reaped the greatest rewards from our winner-take-all economy, and who are troubled by the notion that they may have obligations in return. Not just personal but social obligations—taxation and other duties related to the common good.

What’s missing from the wealth gospel is a breath of reality: Truth is, government and society are involved in the production of wealth, from top to bottom. But what’s really lacking in these preachments is political gratitude. My definition of that—in our social context—is fairly simple, and minimal. Political gratitude is an acknowledgement of the tangible benefits one receives from living in the political community we call the United States of America. If you’re an oil company executive, for example, this means acknowledging the special benefits derived from leasing millions upon millions of acres of public land from the government, at what amount to rates far below any conceivable market value. For everyone, it means acknowledging the many ways that the public aids personal wellbeing and private wealth accumulation.

Aristotle said that if you want to understand what virtue is, look at a virtuous person. On the day after Game 4 of the Series, we could say: If you want to know what political gratitude is, listen to Jonny Gomes. …read more

Were the Shutdown Republicans Prophetic (After a Fashion)?

During the 16-day government shutdown, Tea Party Republicans rose above, or somewhere beyond, earthly politics. Their aim was to stay true to their principles, to be faithful, not necessarily effective. At their meeting behind closed doors on Tuesday, House Republicans began not by calling themselves to order, but by singing all three verses of “Amazing Grace.” In other words, the shutdown Republicans were prophetic in their own way.

By this, I don’t mean they accurately predicted a future state of being. If their stance foreshadowed anything, it was probably some dark days ahead for the GOP. But they were prophetic in the sense that they exhibited the style, if not the substance, of ancient biblical prophecy.

Abraham Joshua Heschel said the prophet is “an assaulter of the mind” who speaks “one octave too high.” This biblical figure is given to “sweeping generalizations” and “overstatements.” He is often “grossly inaccurate” because he concerns himself primarily with meaning, not facts, as Heschel explained in The Prophets, his classic 1962 study.

“Carried away by the challenge, the demand to straighten out man’s ways, the prophet is strange, one-sided, an unbearable extremist,” wrote Heschel, who looked the part of an Old Testament prophet, with his disorderly white hair and conspicuous white beard. The rabbi-philosopher-activist also believed that what a prophet says is radically true. It’s God’s truth, not merely the human variety.

The Tea Party crowd in Congress would seem to fit much of this description, but the truth part is problematic. Normally a prophetic stance involves speaking out for the lowly and oppressed. Prophets do not necessarily take the right stands on every issue, but they stand in the right places, biblically speaking—with the poor and vulnerable.

The job of a prophet is to “strengthen the weak hands,” as the prophet Isaiah declaimed. Arguably, in contrast, the people who brought us the shutdown are more often found strengthening the strong hands, including those of upper-bracket income earners and, at one peculiar turn in the shutdown brawl, medical device makers specifically. And to be fair, many politicians of both parties are often up to these same old tricks of that trade.

Still, the government shutdown tossed light on what you could call, especially if you edit out some biblical material, the prophetic personality.

Posted today in Tikkun Daily. …read more

Lascivious Swedes and other Vindications of Calvin

But what really drew me into Vice was not a lascivious Swede, but an interview with Marilynne Robinson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of acclaimed novels including Housekeeping and Gilead, and one of the more clear-eyed observers of the human situation.

When I saw the headline, “A Teacher and Her Student … Marilynne Robinson on Staying Out of Trouble,” my first thought was that she’s a creative choice for a publication called Vice. Robinson has a fresh and thoughtful take on the theological sensibility of John Calvin, who had a searching eye for all manner of human frailty.

Asked if she had any notable vices, Robinson quickly mentioned “lassitude,” apparently alluding to the second definition of that word—“a condition of indolent indifference.” She recalled a comment by a scientist on why creatures sleep—“It keeps the organism out of trouble.” She added, “So every once in a while I sit on the couch thinking, I’m keeping my organism out of trouble,” suggesting another human foible, that of self-rationalization.

“I do get myself involved in things that require a tremendous amount of work. And of course, I’m always measuring what I do against what I set out to do,” she continued. “My other vices—I cannot have macaroons in the house! I’m a pretty viceless creature, as these things are conventionally defined. On the other hand, one of the reasons I have taken [John] Calvin to my heart is that I can always find vices in the most unpromising places.”

Asked what a vice is, Robinson gave a sort of classically Calvinist response, “I have no idea. Underachievement, I suppose. The idea being that you have a good thing to give and you deny it.”

The Trouble with Seeing

The interviewer, Thessaly La Force (a former student of Robinson’s at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop), evinced no interest in the theological side of Robinson’s ruminations. And the part of the conversation I’ll remember for a while had to do not exactly with a vice, but with the decline of a virtue—simple respect for others and their degrees of goodness. Here’s how she unpacks the problem:

I think that a lot of the energies of the 19th century, that could fairly be called democratic, have really ebbed away. That can alarm me. The tectonics are always very complex. But I think there are limits to how safe a progressive society can be when its conception of the individual seems to be shrinking and shrinking. It’s very hard to respect the rights of someone you do not respect. I think that we have almost taught ourselves to have a cynical view of other people. So much of the scientism that I complain about is this reductionist notion that people are really very small and simple. That their motives, if you were truly aware of them, would not bring them any credit. That’s so ugly. And so inimical to the best of everything we’ve tried to do as a civilization and so consistent with the worst of everything we’ve ever done as a civilization.

On the surface, the notion that human beings are deserving of cynicism might seem to be an instinctively Calvinist (read dour) view. But that’s not how Robinson presents this misunderstood man of the Reformation. She has pointed out elsewhere that Calvinism starts with the idea that human beings are images of God, and every time we see another person, we’re encountering this image. The complication is that humans don’t have very good vision, in that regard.

Every act of seeing “tends to be enormously partial, just given the human situation,” Robinson told my friend and collaborator Bob Abernethy a few years ago. We may see things in a person that bolster our cynicism without seeing much else. And so, in her hands, this Calvinist perspective, this awareness that we never see adequately or exhaustively, “sensitizes you to the profundity of the fact of any other life—that people can’t be thought of dismissively.” And yet, that’s exactly how we are often made to think of the other, courtesy of this human situation. …read more

Of Presidential Vacations and Diminished Leisure

Posted today in Tikkun Daily

At a time when too many people are out of work and too many others are holding down two or three jobs just to survive, it might seem a bit frivolous to lament the lost art of leisure. But leisure—restorative time—is a basic human need. And fewer people are getting the benefit of it, apparently even when they’re on paid vacations.

A new Harris survey finds that more than half of all U.S. employees planned to work during their summer vacations this year—up six percent from the previous year. (Email is a prime suspect in this crime against leisure.) Soon enough, all of us will be taking presidential-style vacations like the one starting tomorrow. That’s when the Obamas arrive on Martha’s Vineyard, no doubt just in time for the president’s first briefing on national security.

In my mind, no one has gone to the philosophical and theological heart of this matter more tellingly than the German American thinker Josef Pieper in his 1952 classic, Leisure: the Basis of Culture.

“The provision of … leisure is not enough; it can only be fruitful if man himself is capable of leisure,” he wrote. In Pieper’s book, workaholics are not the only ones who might be leisure challenged. Some of the most avid vacationers, with clear goals in mind for their getaways, might also be missing the point.

To understand why, one must appreciate the degree to which leisure is a state of mind, “a condition of the soul,” as Pieper styled it. And part of that soul of leisure is effortlessness. “Man seems to distrust everything that is effortless … he refuses to have anything as a gift,” he explained, resting on St. Thomas Aquinas’s teaching that virtue resides in “the good rather than the difficult.”

Those looking for useful tips on how to get more out of their leisure will not find them in Pieper’s meditations. Leisure is not something we do to “get” anything, in fact. According to him, it is worthwhile in itself, not merely a means toward an end.

Examples of such leisure are beside the point, because it’s not so much the activities as the spirit one brings to them. “Messing about” was how G.K. Chesterton put it. So a Chestertonian leisure activity could be almost anything—say, tennis. But the purpose wouldn’t be to “work on my backhand,” as they say.

What is the ultimate form of leisure? Pieper’s answer is not what many would give, including those of us who have experienced the unrest of being with fidgety children in a house of prayer. But for Pieper, the very image of leisure is divine worship.

Celebrating God in a holy place is leisure at its most sublime because it’s something we do purely for its own sake (or else it is not divine worship), Pieper taught. He explained that when people are truly at leisure, they are transported beyond the workaday world into another realm. And this is what transpires in the rituals, he submitted: “Man is carried away by it, thrown into ecstasy.” I’d call it a “mystical” realm or simply a “restorative” one before I’d say “ecstatic.”

It’s getting harder to plumb those depths of leisure, even if you’re blessed with paid vacation time (and increasing numbers of Americans are not). Still trickier, it doesn’t really work if you’re trying. …read more

Sacred Space, at the Corner of Boylston and Berkeley

Prepared for today’s edition of Tikkun Daily.

Two days after the Boston Marathon bombings, Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick was asked in a public radio interview if there would be a permanent memorial to the victims of that horrific act. Patrick understandably felt it was too early to speculate about such a memorial—this was before the dramatic lockdown of Boston and surrounding communities. He went further to say that the most fitting tribute would be to return next year with the biggest and best marathon ever.

That surely would be a testimony to the city’s spirit, but it seems the governor, as a good technocrat, was missing the point. Fact is, people were already finding makeshift ways to memorialize the event. And if past atrocities are a guide, they’ll eventually find a permanent space for that solemn purpose.

If I didn’t know this already, I’d have found out just by standing for a few minutes near Copley Square this past Monday morning, at the intersection of Boylston and Berkeley streets.

Boylston, a crime scene, was still closed at the time. But people stood silently on a sidewalk at the corner, leaning against a police barricade in front of a popup memorial. They gazed at the flowers, flags, candles, handwritten notes, and other items left by anonymous people. They stared at three white crosses in the center of that growing memorial—in remembrance of the three who perished in the twin bombings of April 15. The shrine to eight-year-old Martin Richard was teeming with Teddy Bears, balloons, and children’s books.

People will memorialize, because they know hallowed ground when they see it. It’s extraordinary, when you think about it—how the heinous and the hallowed can share the same space, how a site of evil can be transfigured as holy. But this seems to happen every time. It happened at the Twin Towers, at the Murrah Federal Building at Oklahoma City, at Pearl Harbor, and most profoundly, at Auschwitz. Each of those names marks out a distinct space in the timeless realm of evil. And each space is inviolable.

But how about Boylston Street, or a consecrated corner of it? Is it now part of this geography of the sacred? It is, if you think of such space the way historian Edward Linenthal does. In an interview adapted in a book I did some years ago with Bob Abernethy of PBS’s Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, he said:

My definition of a sacred space is a simple one. Any place that’s capable of being defiled is by definition sacred. You can’t defile ordinary space. Any place that for a group of people is so special that a certain way of being there would be an act of disrespect means that that place is charged with a particular kind of meaning.

Linenthal, who now teaches religious studies at Indiana University, continued:

I tell my students, if they were sitting in the parking lot at K-Mart with a boom box, no one’s going to really care. They might be irritated that the noise is too loud. But if they had a boom box at Gettysburg or in the grove of trees at Shanksville [into which United Airlines Flight 93 crashed on September 11, 2001, in Pennsylvania] or in a church, a mosque, or a temple, it would be considered an act of defilement.

This is why questions about what to do with these places fraught with meaning can be so vexing and contentious. Consider the 9/11 memorial in Manhattan. The decision to store the unidentified remains of victims in an underground repository—rather than a more visible place of tribute—stirred resistance from victims’ families.

Sure enough, a debate erupted this past week over the impromptu memorial at Boylston Street—how to preserve it, where to move it. Such a discussion would have been ludicrous, if this were ordinary space. If it were incapable of being defiled.

And that’s just a prelude. A few days ago, Boston Mayor Tom Menino’s office let it be known that the process of figuring out how to permanently memorialize the bloodshed at Boylston has begun. …read more

Father, Son, and Holy Customer

I’m not naturally a fan of looking at life through the lens of business and management. I’m inclined to do the opposite and see business in the light of other things, like faith and values. I’m not enthused by arguments that government should run like a business, that strong families are like corporate teams, or that students are the “customers” of colleges and universities. Something vital gets lost in the translations.

On the other hand, if St. Ignatius Loyola was right—that God and truth can be found “in all things“—then that has to include business. And I’ve taken a growing interest in management thinking on some valuable questions such as how we change and where ideas come from. (That’s aside from the journalistic fun of turning dissimilar phrases on each other, although one has to be careful when milking sacred cash cows.)

In that spirit, I offer here a piece that ran on Tuesday in Forbes online, “What a CEO Can Teach a Pope,” coauthored by Andy Boynton, a friend and dean of Boston College’s Carroll School of Management, and me. The item was this month’s installment of Boynton’s monthly Forbes blog, “Leading with Ideas” (on which I collaborate).

In the days leading up to the election of Pope Francis, Thomas J. Reese, a noted Jesuit priest and scholar at Georgetown University, was widely quoted as saying that the next successor to Saint Peter needs to be “Jesus Christ with an M.B.A.” That’s a colorful way of putting it, and probably not many Roman Catholics would want a Vicar of Christ to talk like a VP of Strategy. It would be more than curious to hear a papal address about the church’s “core competency” or its need to “ideate” and achieve “synergy.”

Still, Reese’s point is well taken. For one thing, many observers say Francis will have to manage the seemingly unmanageable Roman curia, the Catholic Church’s governing body that has served up such media sideshows recently as the case of “the pope’s butler,” who leaked secret Vatican documents, and a corruption scandal at the Vatican bank. But that’s only for starters.

Let’s look at this for a moment the way a CEO would.

These days the marketplace of belief and unbelief is highly competitive. Religious sects, including Pentecostals and indigenous faiths, are proliferating in places like Africa and Latin America. Other movements—notably, the “spiritual but not religious” phenomenon—are also gaining traction, especially among young adults, including many nominal Catholics. There are growing numbers of “nones,” people who check off “none of the above” when polled on religious affiliation. A pope, one could say, has to come up with ways of bolstering the church’s share of this dynamic market.

Any multinational organization, let alone one with more than a billion customers, has to figure out how to adapt and innovate. But that’s not what the Catholic Church and many other big institutions are good at. The church does many things well—teaching and reaching out to the poor, to name a couple. Timely innovation is not one of them.

Borrowing a page from an illustrious manager, Catholic leaders might do well to consider that ideas for improving the church are everywhere—not just at meetings of bishops or other likely places. Such was the spirit that Jack Welch brought to American business, particularly to General Electric, in the 1980s. Until then, corporate America shared an animus against any idea or product “not invented here,” placing an exclusive priority on the creation of novel ideas within the boundaries of an organization. People were rewarded with bonuses to the extent that they conjured up such notions.

Welch arrived on the scene and set out a new vision. He originally called it “integrated diversity,” but the approach came to be known, more felicitously, as “boundarylessness.” One result was that GE went looking for ideas in the wide corporate world—”Someone, somewhere has a better idea,” he said—and happily adapted these ideas to its specific needs. As Welch once commented in a documentary, “It’s a badge of honor to have found from Motorola a quality program, from HP a product development program, from Toyota an asset management system.”

Likewise, a Catholic bishop might consider it a badge of honor to get an idea about religious education from the North American Jewish Day School Conference, or an insight into the broader culture from a novel written by an atheist. The Catholic Church has always absorbed such influences to some degree, which is how it has transplanted itself into so many cultural contexts over the past two millennia. But keen observers also note that when it comes to making important decisions, the church, like many other organizations, succumbs to the “Not Invented Here” syndrome. Ideas come mainly from within, from top management, and that’s not good.

2,000 Years of Steady Growth

Needless to say, corporations can also learn from the Catholic Church and religious orders such as the Jesuits—about mission, values, and global perspective. But the church does need fresh ideas, and if it’s looking high and low for them, it might as well listen to what concerned people in business management, or recently out of that world, are saying. One of them is Father Tom Doyle, who, in his preordained life, was a consultant with Deloitte & Touche.

To start with, Doyle points out that the church hasn’t exactly been a slow grower, when you take the long view. It began with 12 members—Jesus’ apostles—and now has 1.2 billion adherents around the world. “That’s almost 2,000 years of an annual growth rate of 1 percent,” he told Caitlin Kenney of NPR’s All Things Considered recently, on a light note. “That’s pretty long and pretty incredible growth.”

At the same time, Doyle and others believe the church needs to begin thinking more strategically about its brand, which has suffered in recent years, at least partly because of the sexual abuse scandals. The solution they’re recommending is greater transparency on the part of the institution that emerged last week from the secret conclave.

“This was a huge frustration for all our consultants: a lack of transparency can hurt your brand,” Kenney reported, speaking of Catholic managers and consultants interviewed for her March 6 report. “It can drive away your customers. And as the Catholic Church has recently discovered, this lack of transparency could have much darker implications.” Pointing to the scandals and an erosion of confidence in the church, Kenney added, “People stop trusting that the Catholic Church would tell them the truth.”

For his part, Doyle said he gives the same advice to the church as he would to any company in crisis. “How do you get trust back? You earn it. You have to earn it, right? And so we’re going to have to err on the side of being more transparent about things than we have in the past.”

Most of all, the church and every big institution would do well to put on its listening ears. Listening to various stakeholders—customers, people all levels of the organization, and others—has become a critical part of strategies for designing products and processes in many (though not enough) companies. And the innovation would go a long way in the Catholic Church as well. In its March 18 issue, the Jesuit magazine America editorialized that the church needs to do a better job listening specifically to five groups: the poor, victims of sexual abuse, women, gays and lesbians, and theologians (with whom the hierarchy has an often-frosty relationship).

Listening—in a large and complex organization—is a lot harder than people think. The church may need to get some help with that, perhaps from sympathetic consultants who could facilitate the conversations with different stakeholders. But the good news is that you probably don’t have to be “Jesus Christ with an M.B.A.” to start the ball rolling. …read more

Fumbling and Fallibility at the Vatican

One of the many questions being asked about Pope Francis is whether he’ll be able to get a handle on the unruly and unpredictable Roman curia, the central administration of the Catholic Church. In the past year, that governing body has delivered such spectacles as the case of the pope’s butler, the so-called “Vatileaks” affair, and a continuing corruption scandal at the highest levels of the Vatican bank. Infighting and skullduggery have made it clear that Vatican politics, like the secular variety, can be all too human and at times brutish.

Partly with that in mind, a number of Vatican experts are saying that the new successor of St. Peter needs to have the skill set of a CEO, to manage the unmanageable. I don’t know if that’s necessary (or sufficient). Pope John Paul II was not especially noted for his managerial brilliance, but he was able to transcend the bureaucracy and project a global presence that overshadowed it. The curia was generally trying to keep up with him, not the other way around.

But now, many are asking an oddly necessary question about the most famously hierarchical organization on earth: Who’s in charge there? John Thavis, a longtime Rome correspondent, digs deeply into the paradox in his new book, The Vatican Diaries (Viking). My review of the memoir appears in the current edition of America magazine, and here it is, in full:

After turning the last pages of The Vatican Diaries, I noticed an Associated Press item that began, “The Vatican praised President Barack Obama’s proposals for curbing gun violence.” The report was based on a radio commentary by the Vatican press secretary, Frederico Lombardi, S.J., on Jan. 19. Those who read John Thavis’s vivid recollections in The Vatican Diaries will have cause to be at least initially skeptical whenever they hear that “the Vatican” said this or that definitively about anything.

Recently retired as the longtime Rome bureau chief of Catholic News Service, Thavis argues that the popular image of the Vatican as a monolith, eternally on message, is a myth. On the contrary, it “remains predominantly a world of individuals, most of whom have a surprising amount of freedom to operate—and, therefore, to make mistakes,” he writes.

Re-enter Father Lombardi.

The author tells of an incident when Lombardi, during Pope Benedict XVI’s visit to Jerusalem in 2009, lashed out at “lies” circulating about the young Joseph Ratzinger in Nazi Germany. “The pope was never in the Hitler Youth, never, never, never!” the Vatican spokesman declared to an incredulous press. The problem was that Ratzinger’s Hitler Youth involvement was a matter of historical record. As Thavis explains, Lombardi (whom he describes otherwise as “a gentle soul with a sharp mind”) had overheard the papal secretary remark offhandedly at breakfast that Ratzinger was never an “active” Hitler Youth member. By lunch, the misconstrued comment had become the Holy See’s “latest media fiasco.”

Thavis points to the “fragmented chain of command in what is arguably the world’s most hierarchical organization,” and he relishes the irony. For him, the fumbling and fallibility humanize the institution. But not even the bureau chief was charmed by another episode he recounts that revealed both bungling and deception.

Thavis unfolds the story in a riveting chapter titled “Cat and Mouse,” about negotiations between Rome and the ultra-traditional Society of St. Pius X. Some at the Vatican sympathized with the breakaway order and saw no need to inform top officials that one of four traditionalist bishops whose excommunications were being lifted as part of a reconciliation effort, Richard Williamson, was a Holocaust denier. But most of those who could have averted this particular fiasco—the Williamson affair became one of the biggest religion stories of 2009—were not scheming. They were just snoozing. In the end, the pope admitted publicly that anyone with an Internet connection could have known of the bishop’s bizarre anti-Semitism.

In recent years I haven’t followed Catholic News Service closely, so I’m not sure how much of the book would have been politically incorrect and therefore not publishable in that official news outlet. But I’m guessing Thavis did not often portray Benedict unflatteringly alongside his immediate predecessor, as he does in this memoir.

Here is how the author, with help from Bob Dylan, teases out one contrast at the start of his last chapter, “The Real Benedict”:

The first thing I noticed was the twitching leg. It was dark backstage, but I could make out the slight figure standing at the edge of the platform. He wore a black suit with a white stripe running down the side, and his right leg was jerking up and down involuntarily. It had to be Dylan. And he must be nervous, I thought. Singing for the pope was not an everyday thing.

The performance took place at a Eucharistic congress in Bologna in 1997. Pope John Paul II followed with some reflective riffs on “Blowin’ in the Wind,” evoking the Holy Spirit in motion. Meanwhile, back at the Roman Curia, Cardinal Ratzinger was exuding disapproval, openly disparaging Dylan and other pop icons as “false prophets.” As Thavis writes in another chapter, John Paul traveled to remote lands to be with “tribal dancers in feathered headdresses.” Benedict prefers sitting “in a concert hall filled with dignitaries like himself, listening to Mozart.” John Paul projected a spirit of openness to the wide world. Benedict? Not so much.

Thavis also looks probingly at how the AIDS pandemic has provoked genuine debate within the Vatican about the use of condoms to prevent transmission of the disease. That aside, I was surprised to find little in the book that throws light on global justice issues. During Thavis’s 29 years in Rome, Communism imploded in Eastern Europe, Jesuits and others were massacred in El Salvador, and two popes issued encyclical letters refreshing Catholic social teaching—to mention a few developments. But hardly any of that is recalled in these pages.

Then again, income stratification does not make the most scintillating subject matter for a book subtitled A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Power, Personalities, and Politics at the Heart of the Catholic Church. And I’m glad Thavis has offered this rare, perceptive and highly readable glimpse into a power structure that is less in control than many would have us believe. …read more