Filed under the heading of everybody-and-his-aunt-wants-a-higher-minimum-wage:

And we kept seeing this, something that we thought was wrong. We had to be in an Alice in Wonderland story or something. We would see a “Romney for President” sign and a pro-Tea Party for Congress and “Yes on the Living Wage,” all on the same lawn. And that’s because the idea of a living wage for people and their neighbors to be able to spend money in local stores resonated.

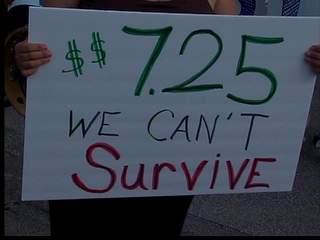

Madeline Janis made this comment in a Bill Moyers PBS interview earlier this month. She led a campaign in Long Beach, California, to enact a startling $13-an-hour minimum wage—specifically for hotel workers in that city. That’s almost six dollars above the $7.25 per hour federal minimum. The measure appeared on the ballot last November and passed easily with 63 percent of the vote.

In the interview, Janis’s main point was that small business owners rallied behind the voter referendum. Their reasoning was, “We want more customers. We want these hotel workers to be able to buy our clothes and our food,” as she related.

But surely, this is an anomaly. Or is it? Small business owners are typically cast as dogged opponents of the minimum wage. Is it possible that most are actually in favor of jacking up the minimum?

It’s more than possible.

Late last month, the organization Small Business Majority released the results of a national poll on raising the minimum wage. Small business owners were asked whether they agree or disagree with the following statement:

Increasing the minimum wage will help the economy because the people with the lowest incomes are the most likely to spend any pay increases buying necessities they could not afford before, which will boost sales at businesses. This will increase the customer demand that businesses need to retain or hire more employees.

Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of those surveyed agreed with this boilerplate case for a more generous minimum wage. What’s more, 67 percent of these business owners agreed with the idea of taking a higher minimum (a dollar figure wasn’t specified) and “adjusting it yearly to keep pace with inflation.”

You might ask: Was the polling sample skewed toward bleeding-heart-liberals, the kind who set up shop in hip districts of Boston and southern California? It doesn’t seem that way. Forty-six percent of the respondents identified themselves as Republican, 35 percent as Democrat, and 11 percent as independent.

People like me often talk about the need to nurture a moral consensus on important questions facing our society. But I find it hard to talk that way, when it comes to the minimum wage. And that’s because we already have a moral consensus on that issue. (See my previous post, on public opinion.)

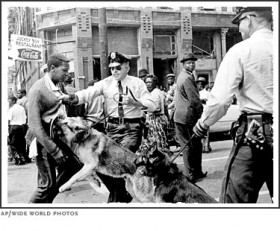

Apparently, most Americans agree pretty much with Martin Luther King: “There is nothing but a lack of social vision to prevent us from paying an adequate wage to every American [worker] … ” But for some reason, our political system today is unable to process this conviction. The minimum wage, adjusted for inflation, remains lower than it was when King fell to the assassin’s bullet in 1968. Special interests are trumping national consensus.

It’s clear that public sentiment in favor of a higher minimum wage is powerful. The problem is that the American people aren’t.

TheoPol will skip the week of Memorial Day and resume the following week. …read more