It’s easy to pick apart claims by some presidential contenders that America is facing an assault from within by adamant secularists, by the elite purveyors of “anti-religious bigotry,” as Newt Gingrich pronounced in his victory speech after the South Carolina primary.

The accusation is often aimed at President Obama, who is, according to former contender Rick Perry, waging a “war on religion,” and who is, according to cooler heads, a theologically serious and sober Protestant. And let’s not overlook a supremely elite institution: the 538-member U.S. Congress, in which there is, by most tallies, one person who goes so far as to label himself a nonbeliever. He is Democratic California representative Pete Stark.

But it’s also worth noting that anti-religious elites do exist and their eschewal of all things spiritual may run deeper than even Gingrich suggested.

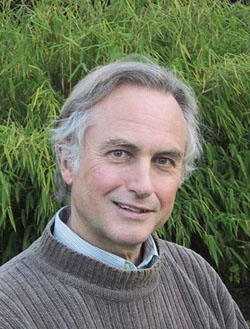

One of the most unequivocal among them is the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins. He not only constantly upbraids the faithful but also serves up an entertainingly bleak and nihilistic view of human existence and the cosmos. Dawkins writes that there is, at bottom, in the universe, “no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.” He forgot to say, Have a nice day!

As a New Yorker by birth and attitude, I feel more at peace with Woody Allen’s old quip that there is in fact meaning in the universe—except for certain parts of New Jersey. (And it was a mere quip. Allen the film director would seem to drift more toward Dawkins’s almost cartoonish view of the cosmic condition.)

Beyond Matter and Motion

The Gingrich forces would be right if all they were saying is that there’s a recently influential cadre of hard-core atheists, who have turned out some lively, readable books like The God Delusion (Dawkins), The End of Faith (Sam Harris), and God is Not Great (by the late great Christopher Hitchens). There does seem to be a brassy challenge to religion and theology issuing from these precincts. The result in recent years has been, for the first time in a long while in the United States, a real debate about faith. Not necessarily about religious conservatives or radical Islam or this or that religious movement, but about faith as such—whether there’s a God, whether there’s a transcendent reality, whether there’s anything in the universe besides matter and motion.

Still, the “New Atheists,” as Dawkins and the gang are dubbed, have been more provocative than they’ve been proliferative.

Many casual observers point to the growing numbers of Americans who don’t identify with any faith tradition; these Americans now comprise about 16 percent of the adult population, according to the most authoritative surveys. But a little over a third of these people affirm that they’re religious even though they’re religiously unaffiliated, and most of the others could be classified as “spiritual but not religious.” Most say they pray regularly or from time to time, as reported in studies such as the Pew Forum’s 2010 U.S. Religious Landscape Survey. These aren’t the shock troops of the New Atheism.

What’s left is a trifling four percent of Americans who see themselves as atheists or agnostics, according to Pew. Maybe they’re the elites who are allegedly subverting our culture, purging religion from public schools and cracking down on religious freedom. But my guess is that not even most of these people would belong to the ranks of religion haters. Besides, the anti-secular warriors are firing mostly in other directions, at Obama and the Democrats, at the schoolteachers and journalists, and others. There are multitudes of believers in all of those directions.

Popular Reruns

Gingrich and others have some real grievances.

They have an argument to make about public school policies that at times go overboard in limiting religious expression. They can point to federal edicts like the Obama administration’s recent move to insist that Catholic colleges, for example, include free contraception services in their healthcare plans for employees. These, however, aren’t skirmishes in the final battle between good and evil. These involve legitimate questions about how to negotiate lines between church and state, between faith and society, between personal conscience and public policy.

Most people know this, but there’s an appreciative audience for the depictions of “war on religion” and “the growing anti-religious bigotry of elites.” We could expect to see those cartoons replayed for much of the presidential primary season. …read more