On this day 50 years ago, African American children began laying their little bodies on the line, in Birmingham, Alabama. Streaming out of schoolhouses by the thousands, they poured into downtown to join in the civil rights demonstrations led by Martin Luther King. My friend Kim Lawton has crafted the best piece of broadcast journalism I’ve seen or heard, on that extraordinary moment in America’s history.

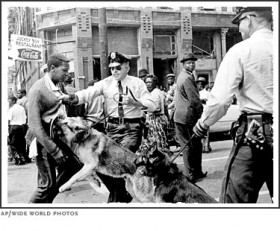

This past weekend she filed the report for PBS’s Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, and one of the people she tracked down was Freeman Hrabowski III, now president of the University of Maryland in Baltimore. He was 12 years old when he came up against the arrayed forces of Bull Connor. The police chief issued the order to turn fire hoses and unleash German Shepherds on the young, nonviolent protesters.

The water came out with such tremendous pressure and, uh, it’s a very painful experience, if you’ve never been hit by a fire hose, and I thought, whoa. You know, I got knocked down and then we found ourselves crouching together and trying to find something to hold onto. People ran, people hid, people hugged buildings or whatever they could to keep the water hoses from just—just knocking them here and there.

After Lawton further described the scene with the police dogs and billy clubs, Hrabowski continued.

The police looked mean, it was frightening. We were told to keep singing these songs and so I’m singing, [he sings] Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me ‘round … keep on a-walk’n, keep on a-talk’n, march’n on to freedom’s land. And amazingly the other kids were singing and the singing elevates when you can imagine hundreds of children singing and you feel a sense of community, a sense of purpose.

And then …

There was Bull Connor, and I was so afraid, and he said, “What do you want little nigra?” And I mustered up the courage and I looked up at him and I said, “Suh,” the southern word for sir, “we want to kneel and pray for our freedom.” That’s all I said. That’s all we wanted to do. And he did pick me up … and he did spit in my face, he really—he was so angry.

For weeks, the protests against Birmingham’s segregated public facilities had been for adults only. Those acts of civil disobedience (marching without permission) had little effect, however. They were petering out by the time of the so-called “children’s crusade.” It was during April of ’63 that King also wrote his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” but that literary classic fell on deaf ears at the time, as Robert Westbrook relates in his piece about the 50th anniversary of the letter, in the April 8 Christian Century. (A half-century later, King’s letter has finally received a proper reply from a group of tardy clergymen, as Adelle Banks reported last month in Religion News Service.)

The children’s crusade turned around the Birmingham campaign—and the nation. It prompted John F. Kennedy, a month later, to go on national television and call for civil rights legislation.

In a recent post, I floated a broader question: How did it happen? How did America change so quickly (there’s room for debate about the degree of change), and on the most polarizing issue of the time, race? I’ll get back to that next week.

Leave a Comment