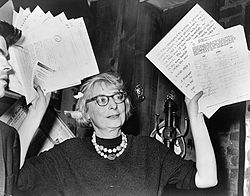

Jane Jacobs, 1961

During the 1950s and 1960s, urban planners had a dream: to remake cities in the image of suburbs. They strove to bring about smoother traffic flow with the construction of urban superhighways, less population density with the dismantling of old neighborhoods, and a strict separation of commercial and residential spaces (read: shopping malls and bedroom communities). The preferred method of effecting these changes was bulldozing.

Places like the West End of Boston, a working-class community of Italians and Jews, were razed and replaced by freeways or, in this case, superblocks of high-rise residential towers and barren, concrete plazas. In Boston, after demolition of the West End in 1958–59, city planners contemplated, with no more affection, another crowded district on their turf—the North End. In New York, plans were readied for the decimation of Lower Manhattan, to clear way for a 10-lane expressway.

When did America begin to turn a fresh eye toward neighborhoods like the North End and New York’s Greenwich Village? This isn’t anyone’s guess. In hindsight, the reassessment began 50 years ago, when a little-known writer who was raising three children in Greenwich Village brought forth a magisterial work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. The 1961 book by Jane Jacobs was tantamount to a precision bombing of city planning agencies nationwide, as Jacobs laid unflinching siege to the then-reigning wisdom that large swaths of cities needed to be rebuilt from scratch.

City planners abhorred urban density, associating it with congestion and unhealthy conditions; Jacobs believed it was essential, partly because more people meant more “eyes on the street,” making all feel safer. She liked to see a mingling of functions—shopping, living, working, leisure—believing diversity made cities come alive. In that first book of hers, she pronounced Boston’s North End, with its cheek-by-jowl dwellings and shops, and sidewalks full of chatter, “the healthiest neighborhood in the city.”

Taking Down Moses

Jacobs died in 2006 at age 89. Her story is a cautionary tale against the tendency to theologize notions that are, at best, mere assumptions. Urban policy makers had turned ideas and practices—such as getting people off the streets for the sake of traffic flow—into solemn doctrines. The chief evangelist of this belief system was Jacobs’s nemesis, Robert Moses, the premier builder of his time and probably any time in American history.

As an urban activist, Jacobs had three epoch showdowns with Moses, beginning in 1958 when she rallied her West Village neighbors against his plan to run a four-lane highway through the middle of Washington Square Park, and ending in 1969. The last and most hair-raising of these projects was what Moses called the Lower Manhattan Expressway, the 10-lane superhighway that was set to pierce through Little Italy, Chinatown, the Bowery, and the Lower East Side, and completely destroy a district then known vaguely as the area south of Houston Street, now the thriving arts and shopping district Soho. The once-invincible Moses lost each of those battles.

Today, Jacobs is venerated widely as the godmother of urban America, the one who fought off the suburbanization of the city. In New York, her legacy is there to see. Just listing the would-have-been Moses projects—the highway through Washington Square Park, the razing of the West Village (yet another struggle), the dismembering of Lower Manhattan—takes the breath away. In each instance, Jacobs was the main stopper.

And many a neighborhood beyond Manhattan that had an appointment with the wrecking crew was also spared, owing in part to Jacobs. The protracted, grassroots campaign against the Lower Manhattan Expressway helped ignite a nationwide anti-freeway movement that frustrated similar designs in, among other places, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Detroit, Milwaukee, Memphis, New Orleans, Seattle, and San Francisco, as Anthony Flint documents in his 2009 book Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took On New York’s Master Builder and Transformed the American City.

Faith in the City

Jacobs eventually took up broader questions of ethics and morality, mostly in her later writings on economics and the environment. But her insights were never as profound as when she was simply noticing the ways in which apartment dwellers, store owners, truck drivers, schoolchildren, and others interacted on city streets—scenes related in Death and Life as part of “an intricate sidewalk ballet.” Like some of the greatest philosophers and theologians—Aristotle and Aquinas, namely—Jacobs reasoned inductively, drawing her conclusions about the world not from abstract notions but from the data of experience and observation. The prominent sociologist William H. Whyte once remarked that her research apparatus consisted of “the eye and the heart.”

A lapsed Presbyterian who forged close conversational ties with theologians at Boston College, Jacobs put her faith in humans and local communities. If she espoused any doctrine, it was their ability to forge vitality out of their spontaneous everyday interplay.

Most of it is utterly trivial but the sum is not trivial. The sum of such casual, public contact at a local level—most of it fortuitous, most of it associated with errands, all of it metered by the person concerned and not thrust upon him by anyone—is a feeling for the public identity of people, a web of public respect and trust, and a resource in time of personal or neighborhood need (Death and Life, p. 56, Vintage Books Edition).

Such faith made it possible for Jane Jacobs to attack the ersatz theologies of her time, with respect to urban policy, and to become the mom who saved Manhattan.

Leave a Comment