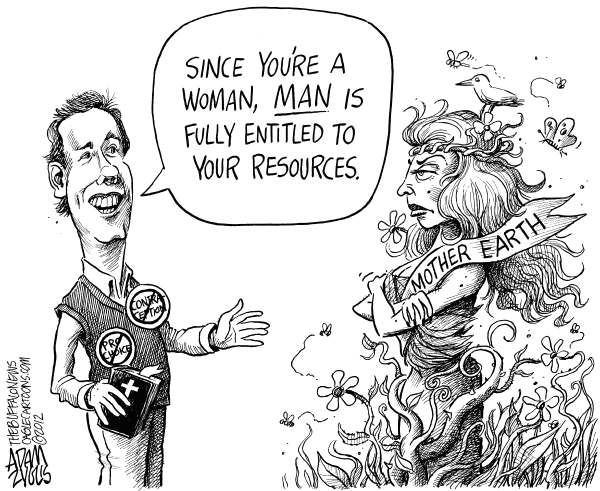

Campaigning in Ohio recently, Rick Santorum opened a new front in the religious and culture wars by declaring that President Obama espouses a “phony theology.” He explained later on Face the Nation that the theology he neglected to initially name was radical environmentalism. Specifically he attacked “this idea that man is here to serve the Earth, as opposed to husband its resources and be good stewards of the Earth.”

Over at The Christian Century blogs, Steve Thorngate took a little comfort in Santorum’s choice of words. “It’s telling that Santorum—pro-coal, climate-change-denying Rick Santorum—didn’t say that people should ‘subdue’ the earth or ‘have dominion’ over it, language (yes, biblical) that tends to conjure up mindless degradation” of the environment, Thorngate pointed out. At Religion Dispatches, Julie Ingersoll reported that Santorum’s casting of environmentalism as its own religion, inimical to Christianity, is “widespread on the religious right and especially in the Christian right wing of the homeschooling movement of which Santorum is a part.”

If ecological consciousness is a sort of religious outlook (and why would it be any more or less so than, say, supply-side economics?), then its main doctrine, according to Santorum, is that human beings are meant to serve nature rather than the other way around. The presidential hopeful also said people are supposed to “care for the Earth,” which to me evokes the idea of service. But the substance of his argument was really that “radical environmentalists” see the human person as subservient to the rest of creation.

That may be a tendentious view of environmental activism, not to mention Obama’s pragmatic bent on these matters. Santorum’s remarks, however, are not completely beyond the orbit of legitimate questions at stake in debates over religion and the environment. Where do human beings stand, in the hierarchy of the universe? Is there a radical, ontological chasm between human creatures and all other living beings? Is there no essential bond between them?

The biblical and theological sources don’t necessarily offer the predisposed answers that would please Santorum, but they’re illuminating in any case.

It’s all “Very Good”

To start with, it’s fair to say that in the Judeo-Christian tradition, human beings have a unique place in the divine scheme of things. “You have made him [the human person] little less than the angels, and crowned him with glory and honor,” the Psalmist says in a song of praise to God’s creation. Praise is given to the Lord for “the work of your finger,” the moon and the stars, sheep and oxen, beasts of the field and all manner of things. The Psalmist is awed by creation, but equally amazed that God would give man and woman so lofty a place—only a little below the angels—in the created order (Psalm 8:6).

That said, the mountains and beasts have an inherent value of their own, quite apart from their usefulness to human beings. In Genesis we read that after fashioning the universe, “God looked at everything he made, and he found it very good.” Religious people have often taken this to mean simply that the creation of man and woman was deemed good, but most theologians agree that “everything” refers to a cosmic reality—the whole of the universe. It’s all very good and worthy of respect.

In the same vein, Christians often speak as if Christ’s redemption extends only to humanity. The New Testament, however, states that all of creation was redeemed, that Christ “reconciled to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of the Cross” (Colossians 1:20-21).

As depicted in these and other spiritual sources, there’s a creaturely commonality across the universe. St. Augustine explained that nonhumans and humans alike could sing together, “We did not make ourselves.” The great philosopher also speaks of a natural world that (like its human counterpart) is intended to pay witness to divine reality:

Ask the loveliness of the earth, ask the loveliness of the seas, ask the loveliness of the wide airy spaces … ask the living things which move in the waters, which tarry on the land, which fly in the air…. Ask all these things, and they will answer: Yes, we are lovely. Their loveliness is their confession.

Diving into Dualisms

Let’s give this the Santorum spin. Are human beings “here to serve the Earth,” or does nature exist purely to service human needs and wants? If you’re coming from a theocentric perspective, a good answer would be “no” on both counts. In an enlightened Judeo-Christian reading, nature isn’t there simply to accommodate humans, or vice versa. Its value is intrinsic, not just instrumental. From that perspective, both human beings and the natural world exist to serve a transcendent God, to fulfill divine purposes. And they are mutually interdependent.

People are unique, but they’re still part of creation and share that existential bond with other creatures, according to a broad interreligious consensus today. By that light, our uniqueness is not an invitation to try to stand above the created world, a status that belongs strictly to the Creator. It is, rather, a call to cooperate with God in the care of creation.

But it’s hard to find the right balance when you’re diving headfirst into dualisms, insisting on a stark choice between “man” and “the Earth.”

Leave a Comment