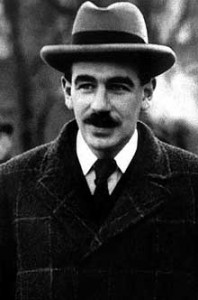

In an illuminating essay in the October 10 New Yorker, John Cassidy teased out the man’s paradoxes in both life and thought. As a young economist with the British government, Keynes had numerous affairs with men before settling down happily with a Russian ballerina. Today he is disparaged by many conservatives as a “socialist,” but he was always a creature of the ruling class. During the Great Depression he declared that when the proletariat revolts, he will stand proudly with the “educated bourgeoisie.”

Keynes applauded what he called “the animal spirits,” the drive to invest and reap wealth. But he pointed out that these instincts are dimmed in a slumberous economy, and his theory—radical at the time—was that the government had to step in “to revive the animal spirits and jolt an economy out of its rut” by way of deficit spending, as Cassidy explains. And so, with his 1936 book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes upended economic policymaking.

Through the decades, deficit spending proved an effective treatment for economic dispiritedness (though Keynes felt the medicine should be applied primarily when the economy is bedridden). He became the intellectual godparent of what is now provocatively known as stimulus spending.

Keynes and the Theologians

There’s much in Keynesian theory that jibes with faith-based reflections on the economy, and much that is, characteristically, paradoxical in that light.

For one thing, it would be hard to find a religious tradition that seriously doubts government’s inescapable role in fostering economic wellbeing. “Indeed, the whole reason for the existence of civil authorities is the realization of the common good,” Pope John XXIII wrote in his 1963 encyclical letter Pacem in Terris.

Different faith groups may tint this teaching in different ways. Catholic social theorists, for example, tend to speak confidently of the virtues of government, the positive good it plays in promoting human dignity and economic justice. Protestant social ethicists might at times look at government more strictly as a necessity than a blessing, a countervailing force against the abuses of wealth (just as private power is such a force against overreaching government). Neither tradition would cheer Rick Perry’s recent campaign promise to make government “as inconsequential as possible” in our lives.

There’s another side of Keynes that’s seldom noted. Unlike many in his tribe, he believed that economics had a purpose beyond economics (beyond, for example, increasing aggregate demand, the goal for which he’s famous). He argued that the ultimate aim of economic activity was to contribute to “the good life,” as Robert Skidelsky relates in his engaging 2009 book Keynes: The Return of the Master. Keynes was speaking generally in the ethical sense of being a good person; he lamented greed in that context. The theologians would agree.

But here comes another Keynesian paradox. He pronounced that the world was not ready for an ethical economy and probably would not be for quite some time until there’s great abundance.

For at least another hundred years we must pretend to ourselves and to everyone that fair is foul and foul is fair; for foul is useful and fair is not. Avarice and usury and precaution must be our gods for a little longer still. For only they can lead us out of the tunnel of economic necessity into daylight.

In other words, for all practical purposes greed is good until the far-off day when it isn’t. The animal spirits will have to remain higher on the ontological food chain than the human spirit; the economy will have to proceed in a moral vacuum. This would be the breaking point between Keynes and the theologians. The latter would say the good economy is not utopian. It’s one that helps people today become “dignified participants in their community,” as the brilliant evangelical Protestant theologian Ronald Sider has framed it.

Greed is not very dignified, from that perspective. Neither is a person’s lack of minimum social goods (to borrow a phrase from Catholic social thought) such as a decent income and affordable access to healthcare. The faith-based question is how to deliver those goods in the here and now. And this brings us back, with a touch more paradox, to the government’s role in reviving the animal spirits. It winds back to stimulus.

Keynes himself was a jocular atheist who would have probably laughed the social-justice reverends out of the room. All the same, he ushered in the Keynesian tools that in hard times past have made the faith-based vision seem a little less distant.

Leave a Comment