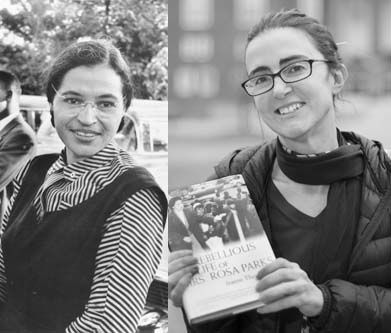

Rosa Parks and Jeanne Theoharis, author of the first scholarly biography of the civil rights legend.

Nonviolence as a tool of social change has often been underestimated and misunderstood. The British thought Gandhi was nuts when he predicted they would simply pick up and leave India without the Indians firing a shot. Black militants sneered at Martin Luther King’s program of nonviolent direct action. And many southern whites assumed African Americans were too undisciplined to collectively turn the other cheek. Or they reasoned curiously that King’s approach was actually violent because it provoked violence in response.

During this Black History Month, new questions about nonviolence and the Civil Rights Movement have bubbled up, thanks to an important new book, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks (Beacon Press), by Brooklyn College political scientist Jeanne Theoharis. Her subject is the presumably quiet, unassuming seamstress who refused to surrender her seat on a bus to a white passenger because her feet were tired. But aside from her act of resistance, Parks was not that person, according to Theoharis.

For one thing, Parks often dismissed the fabled narrative about how she remained seated because of her tired feet. “I didn’t move, because I was tired of being pushed around,” she clarified. As Theoharis shows, black radicalism ran deeply in her family, and she came to sympathize with the Black Power movement that challenged King’s ethic of love and nonviolence.

This storied figure of nonviolent struggle always believed in what she called “self protection.” Like most blacks at the time (including King, very early in the movement), Parks and her husband owned guns. But once the Montgomery Bus Boycott began, she knew many whites were wishing it would turn violent. That would give them “an excuse to dramatically crush the protest,” Theoharis relates.

Parks took a both/and approach:

For her, collective power could be found in organized nonviolence, while self-respect, at times, required self-defense: “As far back as I remember, I could never think in terms of accepting physical abuse without some form of retaliation if possible”…. Parks saw nonviolent direct action and self-defense as interlinked, both key to achieving black rights and maintaining black dignity.

Still, she felt that nonviolent resistance during the bus boycott served as a rebuke to white citizens who regarded blacks as too feckless and “emotional” to carry out such a disciplined strategy. “Parks had delighted in the power of it,” her biographer writes.

The ultimate message about nonviolence is mixed, in the book. Both the author’s narrative and Parks’s own words years later (she died in 2005) suggest a historical revision—a sense that nonviolence was, in the end, not so effective. Here’s Parks:

Dr. King was criticized because he tried to bring about change through the nonviolent movement. It didn’t accomplish what it should have because the white establishment would not accept his philosophy of nonviolence and respond to it positively. When the resistance grew, it created a hostility and bitterness among the younger people, who worked with him in the early days, when there was some hope that change could be accomplished through his means.

This sounds just a little odd to me—as though all hope of racial justice and equality was quickly dashed. There certainly was and remains much unfinished work. But in view of the remarkable social change that took place during the King years, you have to wonder: If he wasn’t successful in effecting change, then who was?

From Montgomery to Cairo

In his Times column on the revised Rosa, Charles M. Blow treated her militancy as a stunning revelation. And it might well be, as far as her children’s-book image goes. Echoing Theoharis, he wrote on February 1, “The Rosa Parks in this book is as much Malcolm X as she is Martin Luther King Jr.”

But does this compelling biography demand a larger retelling of the role of nonviolence in the Civil Rights Movement? Not really.

What it does is throw light on the distinction between nonviolence as an absolute principle and nonviolence as a useful strategy. As his biographers make clear, King knew that African Americans (and people in general) were far more likely to embrace the tactic than the belief system. In King those two perspectives—the practical and the philosophical—merged. More recently they blended also in the witness of other moral and spiritual figures. These included Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who convinced his fellow black South Africans that they and their country had “no future without forgiveness,” and Pope John Paul II, who inspired armless resistance in his native Poland and who spoke of war as an “adventure with no return.”

But it’s fair to say that most who have taken to the streets peacefully—in places ranging from the Philippines to Poland to Egypt—have not been true believers in the gospel of pure nonviolence. They’ve merely delighted “in the power of it.”

I would think that as nonviolence is shown to be effective, many who “delight in the power of it” as a tactical strategy would ultimately be converted to a deeper belief in nonviolence in principle. I’m not sure I even have a good sense of how often this has or hasn’t been the case – but when not, I can only wonder why.

It seems to me that nonviolence, which has always been a part of our history, is a more and more attractive option. At a time when our voting rights, limited anyway, are being chipped away at; when the once-effective strike option for workers has been whittled to nearly nothing; and when the Occupy movement flared brightly but faded, never has it been more important, in my view, for us to exercise our First Amendment right “peacably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Clearly, nonviolence is merely a tool or a tactic. It worked in the U.S. South, South Africa and India in situations in which the disparity of power to deliver violence was lopsided in favor of a white establishment. Violent revolution was possible against the disintegrating Tsarist regime, which was losing a war; but it is not possible against a successfully reigning nuclear power.

As for the context of the black movement for equality, it’s clear that it has not and did not fully succeed. Beyond dismantling a petty and outdated apartheid, The movement did not accomplish much. The workplace, for example, is today more segregated by race than in 1966, when Equal Employment Opportunity rules first went into effect. Advances stopped dead in their tracks in 1980 and then reversed.

Much of what MLK (and Rosa) did accomplish was because he played “good cop” to Malcolm X’s “bad cop.” Let’s not forget that.

Good point about the good cops and bad cops, though I think it would apply more to the later era. The signal achievements–the’64 Civil Rights Act, the ’65 Voting Rights Act, and arguably the equal-opportunity-in-housing initiatives–were good-cop projects for the most part. There’s lots of room for debate about how far they went and how far we’ve come.