Lately I’ve been exploring Vice, not the awful habits (those come naturally), but the international print and online magazine by that name. This week I’ve clicked on pieces with such headlines as “A Muslim’s Adventures in Pork,” “Massachusetts Might Force a Women to Share Parental Rights with the Rapist Who Impregnated Her,” and “You Can’t Just Walk Around Masturbating in Public, Swedish People.” The latter story was about a 65-year-old man who did the deed on a public beach in Sweden but was acquitted on grounds that he wasn’t seeking to harass “any specific person.”

Lately I’ve been exploring Vice, not the awful habits (those come naturally), but the international print and online magazine by that name. This week I’ve clicked on pieces with such headlines as “A Muslim’s Adventures in Pork,” “Massachusetts Might Force a Women to Share Parental Rights with the Rapist Who Impregnated Her,” and “You Can’t Just Walk Around Masturbating in Public, Swedish People.” The latter story was about a 65-year-old man who did the deed on a public beach in Sweden but was acquitted on grounds that he wasn’t seeking to harass “any specific person.”

But what really drew me into Vice was not a lascivious Swede, but an interview with Marilynne Robinson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of acclaimed novels including Housekeeping and Gilead, and one of the more clear-eyed observers of the human situation.

When I saw the headline, “A Teacher and Her Student … Marilynne Robinson on Staying Out of Trouble,” my first thought was that she’s a creative choice for a publication called Vice. Robinson has a fresh and thoughtful take on the theological sensibility of John Calvin, who had a searching eye for all manner of human frailty.

Asked if she had any notable vices, Robinson quickly mentioned “lassitude,” apparently alluding to the second definition of that word—“a condition of indolent indifference.” She recalled a comment by a scientist on why creatures sleep—“It keeps the organism out of trouble.” She added, “So every once in a while I sit on the couch thinking, I’m keeping my organism out of trouble,” suggesting another human foible, that of self-rationalization.

“I do get myself involved in things that require a tremendous amount of work. And of course, I’m always measuring what I do against what I set out to do,” she continued. “My other vices—I cannot have macaroons in the house! I’m a pretty viceless creature, as these things are conventionally defined. On the other hand, one of the reasons I have taken [John] Calvin to my heart is that I can always find vices in the most unpromising places.”

Asked what a vice is, Robinson gave a sort of classically Calvinist response, “I have no idea. Underachievement, I suppose. The idea being that you have a good thing to give and you deny it.”

The Trouble with Seeing

The interviewer, Thessaly La Force (a former student of Robinson’s at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop), evinced no interest in the theological side of Robinson’s ruminations. And the part of the conversation I’ll remember for a while had to do not exactly with a vice, but with the decline of a virtue—simple respect for others and their degrees of goodness. Here’s how she unpacks the problem:

I think that a lot of the energies of the 19th century, that could fairly be called democratic, have really ebbed away. That can alarm me. The tectonics are always very complex. But I think there are limits to how safe a progressive society can be when its conception of the individual seems to be shrinking and shrinking. It’s very hard to respect the rights of someone you do not respect. I think that we have almost taught ourselves to have a cynical view of other people. So much of the scientism that I complain about is this reductionist notion that people are really very small and simple. That their motives, if you were truly aware of them, would not bring them any credit. That’s so ugly. And so inimical to the best of everything we’ve tried to do as a civilization and so consistent with the worst of everything we’ve ever done as a civilization.

On the surface, the notion that human beings are deserving of cynicism might seem to be an instinctively Calvinist (read dour) view. But that’s not how Robinson presents this misunderstood man of the Reformation. She has pointed out elsewhere that Calvinism starts with the idea that human beings are images of God, and every time we see another person, we’re encountering this image. The complication is that humans don’t have very good vision, in that regard.

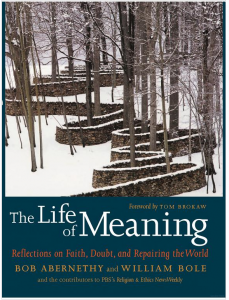

Every act of seeing “tends to be enormously partial, just given the human situation,” Robinson told my friend and collaborator Bob Abernethy a few years ago. We may see things in a person that bolster our cynicism without seeing much else. And so, in her hands, this Calvinist perspective, this awareness that we never see adequately or exhaustively, “sensitizes you to the profundity of the fact of any other life—that people can’t be thought of dismissively.” And yet, that’s exactly how we are often made to think of the other, courtesy of this human situation. …read more