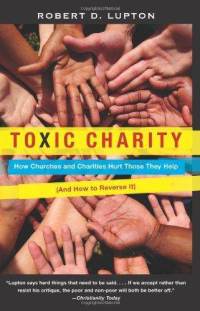

One of the more credible promoters of this view is Robert D. Lupton, author of Toxic Charity: How Churches and Charities Hurt Those They Help (HarperOne). Lupton is not just a true believer in the anti-government gospel, but also a charitable doer. He is founder and president of FCS Urban Ministries (Focused Community Strategies), an evangelical Christian community development agency in Atlanta’s inner city. His book, originally released a year ago, has now appeared in paperback—just in time for Thanksgiving.

During the holidays, the news cycles turn predictably toward stories about the deserving poor and the good causes that serve them well. Lupton and his publicists want the media to crank out a strikingly different story.

“In the United States, there’s a growing scandal that we both refuse to see and actively perpetuate,” he declares at the start of the book. “What Americans avoid facing is that while we are very generous in charitable giving, much of that money is either wasted or actually harms the people it is targeted to help.”

The author points to such basic examples of charity as soup kitchens, clothing drives, and church-sponsored service trips. These are usually counter-productive, he asserts, because they breed dependency and “destroy personal initiative” as well as family structures.

The argument is familiar enough, when it comes to government social programs. But the follow-up is usually that private charities are the way to go, because they’re more responsive to local needs, or because they don’t use taxpayer money (although they often do). Lupton doesn’t go there.

He does allow that some charitable work is nontoxic and necessary—disaster relief being his chief example. And he speaks up for “community development,” including job placement and affordable housing in cooperation with for-profit developers. This aspect of his argument is reasonable, though not very interesting: Such efforts have become commonplace among private service organizations.

Beyond that, charity encourages “ever-growing handout lines,” Lupton writes. He calls for shuttering food pantries and replacing them with food coops that sell shares to the poor; canceling the clothing drives and setting up thrift stores. In his view, such draconian measures are in order because the poor will just use their Thanksgiving baskets and secondhand socks to bolster what he terms their “lifestyle poverty,” their thriftless, workless ways.

Lupton seems to believe that the American poor are almost unique in this way. For example, he puts in a good word for micro-lending projects in the Third World, but then questions their applicability to the United States. And the reason he gives is that in our country, “the welfare system has fostered generations of dependency and has severely eroded the work ethic.” The American poor “assume that their subsistence is guaranteed” because of public and private largesse, so they don’t exercise personal responsibility.

I’ve ceased being surprised by things people say about the poor and the lower 47 percent of the economy. But part of what strikes me about Lupton’s critique is his lack of any discernible interest in the demographics of poverty—the facts, in other words.

The Poor Are Not One Group

For those pesky details, I called up Candy Hill (whom I quote in the November 18 edition of Our Sunday Visitor). She is senior vice president for social policy at Catholic Charities USA, a national umbrella organization.

To start with, Hill told me that many who knock on the doors of local Catholic Charities do so for the very first time. And they usually come looking for food. Typically, they have lost a job, suffered an illness, or faced some other crisis. They can put off paying the utility bill or mortgage but cannot go long without eating. “We see them because they’re hungry,” she says, adding that elderly people on fixed incomes are also familiar faces at soup kitchens.

According to Hill, these people form a sizeable swath of charity recipients—the suddenly and temporarily poor. Lending them a hand doesn’t make them dependent. It usually gets them back on their feet.

A second subgroup consists of those with lifelong disabilities and impairments. “We help them reach their full potential,” said Hill, alluding to such efforts as job training for the tasks they’re able to perform, but Catholic Charities does so “with the understanding that they’ll never be totally independent.” They’ll always need help from both government and charities.

The third type of recipient cited by Hill is the chronically poor, in need of continual services. On the surface, they supply Lupton with his dependency thesis, although he draws little distinction between them and others in the fluid ranks of the poor. And they’re a distinct minority: Approximately 25 percent of those in poverty have been poor for three years or longer, according to a plethora of studies cited by Catholic Charities.

For these people, Catholic Charities offers what Hill described as a “continuum of care,” in which case workers evaluate their needs at various stages. Some typical services include job training, parenting classes, rental assistance, and prescription drugs for chronic illnesses.

But she is reluctant to assign even these cases to Lupton’s all-encompassing category of “lifestyle poverty.” She notes, for example, that a growing number of the long-term poor are living in homeless shelters and holding down jobs, sometimes two or three—their wages too low for rent. “They’re some of the hardest working people I know,” said Hill, who previously headed Catholic Charities of Monroe County in Michigan.

Contrary to the impression given by Lupton, charities that work with these people aren’t flush with cash. Contributions have continued to dip throughout the fragile economic recovery. As Hill points out, food pantries nationwide have been cutting back on bread loaves, soup cans, and other items tossed into food bags, even as the need rises with many families trying to scrape together a holiday meal.

Now, Lupton is offering one more reason, and not a particularly good one, to shrink those Thanksgiving baskets even further.

TheoPol will skip Thanksgiving week and return on Thursday November 29.