What happens when a prayer is censored?

As Ruth Langer inspected the grainy images of medieval prayer books, she began to notice that some words had been blotted out with ink or smeared as though with the lick of a finger—signs of censors at work.

Journalist, Author, Analyst

As Ruth Langer inspected the grainy images of medieval prayer books, she began to notice that some words had been blotted out with ink or smeared as though with the lick of a finger—signs of censors at work.

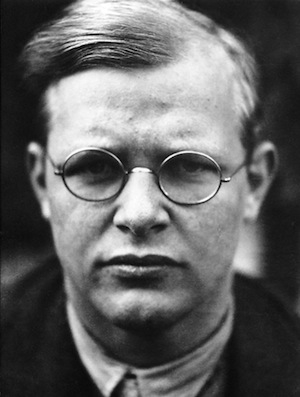

Bonhoeffer was on the menu this past February at the always-strange National Prayer Breakfast in Washington. During his keynote speech, bestselling conservative author Eric Metaxas claimed that George W. Bush had recently read his 2010 biography of Bonhoeffer. Then he handed a copy of the 608-page doorstop to the man sitting a few feet away from him—Barack Obama—and said jejunely, “No pressure.” With Obama straining to smile, Metaxas also suggested that legal abortion was akin to Nazism.

Bonhoeffer is in perpetual “vogue,” as the Christian literary review Books & Culture has pronounced. That’s an ironic way of commending the clergyman who railed against superficiality in all matters religious, and could not indulge what he called “cheap grace,” the easy path to discipleship.

One lesson of Bonhoeffer’s witness is that the Christian Church must always be a church, must always pay ultimate loyalty to God, not to false gods, which for Bonhoeffer included Nazi ideology. While still in his twenties, Bonhoeffer, who began his theological career at the University of Berlin, emerged at the forefront of the Confessing Church, an ecclesial movement that arose in 1934 with a call for German Christians to resist the Third Reich.

There are incongruities in the Bonhoeffer story, and the most tantalizing has to do with the choice that sealed his martyrdom. He was a pacifist who never renounced his belief that violence is antithetical to Christian faith, as revealed by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount. And yet beginning in early 1938, he joined in a succession of conspiracies to murder Hitler, while spying for the Allies. This turn from pure nonviolence has led some, including conservative Christians like Metaxas, to fancy that Bonhoeffer would have cheered America’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

But this conjecture seems to miss an essential point about the man and his thinking. Scholars note that Bonhoeffer—who recorded his thoughts in letters smuggled out of prison—did not rationalize his actions other than to say that the situation was extreme. The theologian felt that his decision to join in the conspiracies against the Fuhrer “was not justified by law or principle, but rather was a free act of Christian responsibility, for which he threw himself on the mercy of God,” Clifford Green, a Lutheran minister and eminent Bonhoeffer scholar who taught at Hartford Theological Seminary, told me a few years ago.

This ethic may be too subtle for retail politics, but it’s powerful still. In the most acute moral emergencies, we can do what we have to do, to stop a tyrant or head off genocide. But let’s not fool ourselves. There will be plenty to atone for, and little cause for self-congratulation.

What is indisputable is that Bonhoeffer accepted “the cost of discipleship,” which are the title words of his 1937 classic. On the morning of April 9, 1945, at the Flossenburg concentration camp, he was stripped, led naked to the gallows, and hung for his part in the plots to assassinate Hitler. At that moment, historians say, Bonhoeffer could hear American artillery in the distance.

He was 39 years old. Two weeks later, the Allies liberated the city. …read more

On September 10, 1977, France raised the 88-pound blade of its guillotine one last time and let it drop on a Tunisian immigrant who had sexually tortured and murdered a young French nanny, lopping off his head in just a fraction of a second. After that, a cry of “off with their heads” heard anywhere in the Western world would likely suggest little more than a taste for metaphor, not a thirst for blood. And soon, all manner of executions, not just the heads-roll variety, would be declared illegal throughout Western Europe. In due time scores of countries elsewhere—from Mexico and the Philippines to Cambodia and Rwanda—would put away their death penalty statutes. Only the rare developed nation would kill to show that killing is unacceptable.

The United States would be rare. Lethal injections, electrocutions, and other means of judicial death would offer an eye-popping display of American exceptionalism. The death penalty is still all too with us in America, and only eight other countries, with not a democracy among them, executed more than two or three people last year. That said, in recent years we have become less exceptional on this score.

The latest case in point is Connecticut, where lawmakers voted yesterday to abolish new death sentences. Governor Dannel Malloy, a Democrat, has vowed to sign the measure, which will make Connecticut the fifth state in the past five years to forsake punishment by death. (The others are New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, and Illinois; California voters will probably have their say at the ballot box in November.)

The biggest story, however, is not about the handful of states that are shuttering their death houses altogether. It’s about the slow death of capital punishment throughout the country, though I’d lay emphasis on slow. The numbers of executions as well as new death sentences have been falling steadily in recent years. In 2011, 43 people were executed nationwide, a 56-percent drop since 1999, according to the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington.

Even Texas has been less eager to administer the heart-stopping potassium chloride and other lethally injected drugs. Texas extended the death protocol to 13 inmates in 2011, compared to 24 two years earlier. That’s just one way of sizing it up, though. Another way is to note that if Texas were a country, it would rank eighth in reported executions worldwide, right behind North Korea and the rest of the United States, but way ahead of countries such as Somalia and Afghanistan.

For decades many in the United States have opposed capital punishment on moral and religious grounds. Such a culturally conservative force as the American Catholic hierarchy has repeatedly denounced the practice as a violation of the sanctity of human life. To me, one of the most cogent moral arguments against the death penalty came from Pope John Paul II. He argued time and again that the only possible justification for capital punishment (or any use of deadly force) would be strict self-defense—which rules out the death penalty in almost every conceivable circumstance. That’s because, as John Paul noted, there are many other ways of protecting society against a killer, ways known collectively as the modern penal system.

As someone who dislikes capital punishment for more or less those reasons, I’d be happy to give the credit for its decline to the abolitionists and their excellent principles. But I’d be kidding myself.

It’s not moral revulsion against the whole idea of capital punishment that has thinned the execution ranks. It is the well-founded fear of executing the innocent, a real possibility brought to light not by moral arguments but by the evidentiary wonders of DNA, which has led to multiple exonerations in recent years. Polls show that most though a declining number of Americans still support capital punishment at least in theory, and the basic reason is that most inmates on death row are not innocent. They’re guilty as hell.

So, Americans haven’t yet had a moral conversion on this issue. And that’s okay. In a pluralistic society, citizens—even those on the same side of an issue—will bring diverse values and considerations to the table of public conversation. When it comes to the death penalty, some worry about faulty procedures that could lead to wrongful execution or simply about the costs of seemingly endless appeals. It’s the job of others including the theologically motivated to add moral principles to the mix, and to do so with humility and what the Declaration of Independence refers to as a “decent respect” for the opinions of humankind. It’s fair to say that many different opinions have coalesced to put the greatest pressure on capital punishment in decades.

What might eventually tip the scales toward abolition is not liberal outrage but conservative caution. True, many conservatives have taken the untenable view that government—which, in their minds, is incapable of adequately performing a simple task like creating a construction job or an affordable housing unit—is somehow so adept and infallible that it can be trusted to make ultimate decisions about life and death. This logic is no longer flying with increasing numbers of Americans, however. And they include many who lean right.

The last words here go to Richard Viguerie, a father of what used to be called the New Right, now known as the Tea Party.

Conservatives have every reason to believe the death penalty system is no different from any politicized, costly, inefficient, bureaucratic, government-run operation, which we conservatives know are rife with injustice. But here the end result is the end of someone’s life. In other words, it’s a government system that kills people (his emphasis)….

The death penalty system is flawed and untrustworthy because human institutions always are [my emphasis]. But even when guilt is certain, there are many downsides to the death penalty system. I’ve heard enough about the pain and suffering of families of victims caused by the long, drawn-out, and even intrusive legal process. Perhaps, then, it’s time for America to re-examine the death penalty system, whether it works, and whom it hurts. …read more

William Bole is a writer with a background in both daily journalism and academia. He writes at the three-way intersection of religion, public affairs, and the arts, while often steering into other areas of interest, especially higher education and management. In addition, he teaches nonfiction writing at Boston College, where he serves primarily as director of communications at the Carroll School of Management. … read more

By Bob Abernethy and William Bole, with a Foreword by Tom Brokaw

Nautilus Book Awards

Gold Winner 2008

William Bole is a writer with a background in both daily journalism and academia. He writes at the three-way intersection of religion, public affairs, and the arts, while often steering into other areas of interest, especially higher education and management. In addition, he teaches nonfiction writing at Boston College, where he serves primarily as director of communications at the Carroll School of Management. … read more

Welcome to TheoPol—a writing project that ran for four years. During much of that time, it featured weekly snapshots of interconnections between theology and politics. The questions—as to what these connections are, or should be, and whether there should be any at all—remain current. ...read more

"A thoughtful new blog"

— Bill Tammeus, Faith Matters

>> read the review.

“A great gift for relating [ideas] with a storyteller’s instinct and wit.”

— Tom Roberts, National Catholic Reporter

>> read the review.

Copyright © 2026 William Bole

PH: 978.475.2474

Email: info@WilliamBole.com

Site design by: Blue Iris Webdesign