William Bole is a writer with a background in both daily journalism and academia. He writes at the three-way intersection of religion, public affairs, and the arts, while often steering into other areas of interest, especially higher education and management. In addition, he teaches nonfiction writing at Boston College, where he serves primarily as director of communications at the Carroll School of Management. … read more

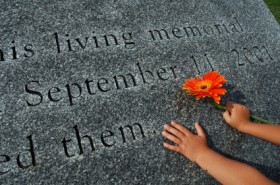

Evil Acts, Sacred Places

This is one way of sizing up the contention surrounding the 9/11 Memorial and Museum that opens this Sunday at the World Trade Center site.

Nearly 3,000 people perished as the Twin Towers crumbled on September 11, 2001, and the remains of more than 40 percent of them have not been identified. Many families of those victims have pushed for a common burial place at Ground Zero, a monument not unlike the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington Cemetery.

They thought such a tomb, there for all to see, could serve as a dignified final resting place for their loved ones. Instead, the remains will be stored in a room behind a wall in the underground 9/11 museum that will open together with the above-ground memorial. The words of Virgil will be inscribed on the wall: “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.”

Some 9/11 relatives say they’ll never go there. In essence, they argue that the remains repository—seven stories below ground in a museum that is considering charging for admission—has not been scaled to the sacredness of Ground Zero. They believe the storage plan is a desecration of the whole site.

Designers of the memorial, as well as other 9/11 families, disagree.

They point out that inside the concealed room, medical personnel will continue the task of identifying remains—a meaningful activity. And they say the above-ground memorial, including a plaza with waterfalls and two reflecting pools, will constitute hallowed ground. Bronze panels around the pools will bear the names of all 9/11 victims.

Translating the Sacred

What stirs little contention is the understanding behind the misunderstanding, the theology behind the politics. By and large, the dissenting families and the memorial’s creators agree that this tract of unspeakable evil is in fact sacred ground and ought to be handled as such. They clash only on the particulars of how to flesh out the sacredness.

For instance, on its web site the 9/11 Memorial and Museum acknowledges the volatility of questions about how to return the unidentified remains to “the sacred ground of the World Trade Center site.”

From one perspective, this is not the most intuitive theology. In a traditional formulation, a place becomes sacred when God intervenes to demonstrate his wondrous ways; it becomes a point of entry into the divine world. This would be a dicey reading of the horrific events that transpired ten years ago. It would also be a strictly religious one.

There is, however, another way of parsing this theology.

Simply put, sacred space is fraught with special meaning. It opens the way to a transcendent truth and reality that is qualitatively different from the surrounding ordinary space. This is more or less the approach taken by the Romanian scholar Mircea Eliade in his 1957 classic, The Sacred and the Profane: the Nature of Religion.

In Danger of Defilement

In addition, such a space is easily desecrated. The insightful religious studies scholar Edward Linenthal underscored this in an interview conducted by Kim Lawton of the PBS television program Religion and Ethics Newsweekly, aired on the first anniversary of 9/11.

My definition of a sacred place is a simple one. Any place that’s capable of being defiled is by definition sacred. You can’t defile ordinary space. Any place that for a group of people is so special that a certain way of being there would be an act of disrespect means that that place is charged with a particular kind of meaning.

A belief in the sacred appears to be part of the common theological sense of most Americans. That a single space could encompass both evil and the holy is also not perplexing to them.

This perspective brings together people ranging from relatives of firemen who fell on 9/11 to architects of the new memorial. It could also pull them furiously apart when some interpret “a certain way of being there” as a desecration of that holy ground. …read more

The Peace Front

Religious groups stake out a wider role in violent conflicts.

Religious groups stake out a wider role in violent conflicts.

On Sept. 11, 2001, a cadre of young Muslim men hijacked planes and, perhaps with visions of black-eyed virgins in Paradise, crashed them into the Pentagon and the twin towers of the World Trade Center, acting supposedly in the name of their religion. Within hours of these atrocities, Top 40 radio stations across the United States began playing John Lennon’s anthem “Imagine,” which supplied what many saw as a soundtrack of hope and harmony in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks. The lyrics longingly envisioned “all the people, living life in peace.” But with a disquieting relevance to the suicide attacks, Lennon had also pondered, “Imagine there’s no heaven…and no religion, too.”

Since then commentators have fleshed out this contemplation of a religion-free world. “Imagine no suicide bombers, no 9/11…no Crusades…no Israel/Palestine wars…no Taliban,” wrote the prominent atheist and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins five years after the towers crumbled. This past December, 30 years after the ex-Beatle was gunned down by a deranged fan, the comedian and television personality Bill Maher, alluding to religious strife in general, sent a message to his fans on Twitter: “Remember Lennon said ‘Imagine NO religion.’ Honor what he wrote—it holds up.” These and other secularist screeds have tapped into a larger feeling that religion usually is a cause of violence rather than an agent of peace helping to resolve and heal conflicts. …read more

Ten Years After

Filipino General Raymundo Ferrer: In the midst of a U.S.-backed war against Islamic extremists, he wields the soft power of forgiveness and reconciliation.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I was working on—of all things—a book about forgiveness and international politics.

I was at my desk at home, and spoke briefly by phone with a Georgetown University colleague who said she had just overheard something about a plane crash in Lower Manhattan. Oblivious to the scale of the catastrophe and the cascading irony of my theme, I kept my head down and dug into case studies of political forgiveness around the world.

That I might be onto an idea whose time had passed almost as soon as it arrived did not set in until the next day when I heard from friends who had seen or been close to the horror in my hometown. They were, as they had every right to be, unforgiving.

Did it make sense to continue talking about forgiveness as a geopolitical option, as I and many others did? A decade into the war on terrorism, is forgiveness a useful way to think about international relations and conflict resolution?

A Political Theology of Forgiveness

The answer depends on your concept or theology of forgiveness.

There is the pietistic view that assigns forgiveness to the realm of personal faith. In this spiritual milieu, forgiveness is an unconditional act. It happens when one person musters the inner strength to say to another, “You’re forgiven,” or otherwise buries the hatchet, once and for all.

This concept of forgiveness does not travel well from faith to politics. No one should hold her breath waiting for such a sweeping, unilateral act of mercy involving extremely fractious groups. And it’s easy to miss the real story, when forgiveness is understood in that literal fashion.

Then there is a political theology of forgiveness articulated by such thinkers as Donald W. Shriver, Jr., in his 1995 book, An Ethic for Enemies. In his rendering, forgiveness is not a single act; it is a process with a range of transactions that look to a new political future together.

Truth—the acknowledgment of wrongdoing or misguided thinking—is one such transaction. Another is the decision to steer away from revenge and retribution.

There should also be clear signals of a desire to eventually repair the fractured social relationship. In the years leading up to 9/11, such strategies helped transform conflicts in places ranging from South Africa and Rwanda to Northern Ireland and South Korea.

Conditionality is a must, in the politics of forgiveness.

For instance, at the end of white minority rule in 1994, South Africa’s black leadership offered amnesty to human-rights violators—with one stipulation. Those perpetrators had to publicly divulge the truth about atrocities committed under the apartheid system. Without conditionality, forgiveness loses a vital link to justice and restitution.

Enter Islam

What has altered this picture distinctly since 9/11 is the challenge of Islamic extremism. Is forgiveness an improbable way to conceive of a response to such a worldwide threat? Perhaps, but some practitioners of conflict resolution have found ways to begin reconciling locally with radical Islamic movements.

Among the most unlikely of them is General Raymundo Ferrer of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, whose command covers most of Mindanao, the nation’s second-largest island. The Filipino military has waged counterinsurgency campaigns against Islamic rebels in the southern islands since the 1970s, working hand in glove with the United States military since 9/11. During this past decade, however, Ferrer began to realize that an absolute reliance on hard power was foolish and misguided.

In his rethinking, the notion of a final military victory by the Armed Forces became far-fetched. He began repairing ties with long-aggrieved Muslims in little ways. For example, Ferrer ordered his troops to point their guns down and smile at Muslims when passing them on the street, as political scientist Maryann Cusimano Love describes in a case study published earlier this year by Georgetown University’s Institute for the Study of Diplomacy.

Ferrer himself began striking up conversations on the sidewalks near his post in Basilian, Mindanao, meeting the locals, among them a Catholic social worker who wasted no time linking him up with interfaith peace activists. These are Christians and Muslims who had begun holding grassroots interreligious dialogues between members of their communities years earlier.

They, in turn, encouraged him to sign up for “peacebuilding” training conducted jointly by Catholic Relief Services, the American-based international aid organization, and the Mindanao Peace Institute, a Mennonite-Catholic collaboration. Ferrer did so in 2005, in the face of resistance from both fellow generals and church human-rights activists who distrusted the military.

Soft Power

Since then the general has sent his colonels to classes in “nonviolent communications,” mediation, religion and culture, reconciliation, and other peaceable subjects.

Love’s case study throws light on the possible utility of forgiveness—understood as a way of reconstructing social relationships, piece by piece. Stemming from his acknowledgment of misguided thinking, Ferrer’s overtures were essentially signals of his commitment to rebuild relations with Muslim populations. Those are transactions of political forgiveness.

Together, the Filipino government and Islamic rebel movements have made strides toward reconciliation, but this story continues, partly due to the splintered nature of those insurgencies.

Approaches involving truth telling, forbearance from revenge, and empathy have entered into the toolkits of many religious and secular peacemakers around the world. Whether these initiatives multiply will depend in part on leaders like a Filipino general who is not afraid to wield the soft power of forgiveness and reconciliation. …read more

About TheoPol

Welcome to TheoPol—a writing project that ran for four years. During much of that time, it featured weekly snapshots of interconnections between theology and politics. The questions—as to what these connections are, or should be, and whether there should be any at all—remain current.

In one light, theology and politics should have little to say to each other.

Theology is reflection upon the experience of faith. It is the way we think about the ultimate, whatever our ultimate cares and concerns may be. Politics rightly deals with sublunary questions, like how to tackle a public problem at a particular time, given the constraints and opportunities.

Theology can be cast as a view from the cosmos. In comparison, politics is a street-level transaction.

In another light, almost everyone has ultimate concerns.

Religious adherents and secular souls alike have embedded values, whether these are declared or not. Such values and assumptions will surface in politics, particularly during periods when critical masses are moved by the immaterial dimensions of life, struggle, and conflict. This appears to be one of those times.

TheoPol looks at the phenomenon through a journalistic lens. The interconnections are teased out from current affairs; also highlighted are stories of those who have grappled with the question of where to set the dial between theological conviction and political action.

Of particular interest is the cast of theological characters who coalesced during the civil rights and antiwar campaigns of the 1960s. They were present at the creation of the modern theology-and-politics movement and include iconic figures such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, the Rev. William Sloane Coffin, the Rev. Richard John Neuhaus, and Father Daniel Berrigan.

They and many others, of varying theological strains, are counted among the TheoPols.

TheoPol is authored by William Bole.

The Idea Hunter

How to Find the Best Ideas and Make Them Happen

By Andy Boynton and Bill Fischer, with William Bole

The Idea Hunter challenges many assumptions about how great ideas are discovered and who discovers them. Drawing on a plethora of academic research as well as interviews, the authors show that outstanding business ideas do not spring from innate creativity or necessarily from the minds of brilliant people. Rather, breakaway ideas come to those who are in the habit of looking for such ideas—all around them, all the time.

These are the Idea Hunters. Such people do not buy into the starry-eyed notion that the only great idea is a pristinely original one. They know better. They understand that high-value ideas are already out there, waiting to be spotted and then shaped into an innovation. …read more

Forgiveness in International Politics

… an alternative road to peace

The whole notion of forgiveness—as a geopolitical prospect—can seem counterintuitive in an age when people crash planes into skyscrapers. And yet, forgiveness has shown itself to be real enough, and strategically useful in helping to repair relationships that have been long sundered in a number of fractious societies.

Based on a seven-year research and dialogue project conducted at Georgetown University, Forgiveness in International Politics presents case studies of conflict transformation in South Africa, Northern Ireland, Bosnia, and other nations. The book explains how political leaders such as South Africa’s Nelson Mandela and South Korea’s Kim Dae Jung helped heal political wounds by engaging in “transactions of forgiveness,” which include gestures of forbearance from revenge and public acknowledgements of wrongdoing.

Such acts and interventions have pointed the way toward a “politics of forgiveness,” according to the authors. …read more

https://williambole.com/forgiveness-in-international-politics/

Organized Labor and the Church

Reflections of a “Labor Priest”

By George G. Higgins, with William Bole

In this engaging and highly readable work, Msgr. George Higgins—the dean of American Catholic social action—draws on nearly 50 years of direct involvement in the cause of working people and their unions.

Together with his coauthor William Bole, Higgins writes as both eyewitness and seasoned observer. He revisits the significant moments in the 20th century encounter between religion and labor. He introduces us to some of the great labor leaders across the decades: John L. Lewis, Philip Murray, Walter Reuther, George Meany, Cesar Chavez, and others. …read more

Religious groups stake out a wider role in violent conflicts.

Religious groups stake out a wider role in violent conflicts.