This student is not alone. In December the New York Times ran a piece about Facebook resisters: people who refuse to join or choose to drop out. The prototype for the story was a premed student in Oregon who had a chance encounter with a woman in an elevator. He had never met her, but through Facebook knew that she came from a remote island in Washington State and had recently visited Seattle’s signature tower, the Space Needle. He had also seen family pictures of her older brother.

“I knew all these things about her, but I’d never even talked to her,” the college student told Jenna Wortham of the Times (he and the woman in the elevator had real friends in common). “At that point I thought, maybe this is a little unhealthy.”

These Facebook defectors are grappling with questions both personal and philosophical—questions enlightened by Aristotle more than two millennia ago in his immortal Nicomachean Ethics. What is friendship? Who shall I count among my friends, and why?

At Boston College, political science professor Robert C. Bartlett teaches classes in Aristotle’s Ethics, and he finds that students are most drawn to Books VIII and IX, which deal with numerous aspects of friendship. These days, the question that brews in class is more or less: How many of my 675 friends on Facebook would be considered actual friends by Aristotle? The students can take a good guess at the answer if they’ve kept up with the reading.

Varieties of Friendship

Friends fall into three basic categories, according to Aristotle. There are friendships of utility, based largely on what the friends could do for each other. There are friendships of pleasure, which often bring people together because of a shared hobby or interest. And there are friendships of virtue (Aristotle’s favorite): You like someone because he or she is a good person. You and your friend help each other lead the good, as in ethical, life.

Which of these would best describe some typical Facebook friends, like the kid you ran track with in high school and haven’t heard a lot from since? Bartlett’s sober answer is: none.

Together with University of Houston political science professor Susan D. Collins, Bartlett analyzes Aristotle’s view of friendship in a commentary included in a new and well-received edition of the Ethics, translated by them and published by the University of Chicago Press. (I write about the translation project in the current issue of Boston College Magazine). One of their basic conclusions is that friendship, in Aristotle’s understanding, is active. A friend is a part of your life and has been for some time. As Bartlett and Collins put it, “Friends go through life together.” They wish the best for each other and do things for each other’s sake. (In that sense, all friendships call for virtue, even those based largely on utility and pleasure). And friends “share in sufferings and joys,” the two scholars add.

To the student who wonders about his hundreds of Facebook friends, Bartlett will say they can’t all be real friends; each one can’t be a meaningful part of your life. If that’s true, then what are these friended folks? Simply put, they’re acquaintances (at best), Bartlett submits.

Two Cheers for Acquaintanceships

Many of us would not want to end the conversation right there.

For one thing, acquaintanceships are far from valueless. They can be glimpsed in the rows of parents who unfold their chairs and chat pleasantly on the sidelines at soccer games, and the neighbors who together keep vigilant “eyes on the street,” to use Jane Jacobs’s evocative words. These are not necessarily friends, but they encounter one another along some of life’s familiar pathways. With any luck they help nurture a feeling of civic friendship.

And how should we think about the people with whom we once journeyed more profoundly through life? It’s hard to let go of the belief that our high school or college buddies from long ago are still our friends, even if we know little about their lives today that’s not posted on Facebook. As Bartlett notes, Aristotle assigns the tender feelings we may have for such people to the category of “goodwill,” not friendship. I hear you, Aristotle, but grope for a word richer than “goodwill” to account for the bonds that were, and—in ways not easy to name—continue to be.

All the same, everyone who desires a fuller appreciation of these questions will find a wise and discerning friend in Aristotle. “Without friends,” he writes in the Ethics, “no one would wish to live, even if he possessed all other goods.” …read more

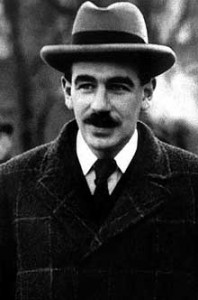

It has been said that economists are people who work with numbers but don’t have the personality to be accountants. One number-cruncher who put the lie to this witticism was John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), who had the personality of a rock star. He was given to grand pronouncements, as when he wrote a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw, in 1935, predicting—correctly—that the book he was writing would “largely revolutionize the way people think about economic problems.”

It has been said that economists are people who work with numbers but don’t have the personality to be accountants. One number-cruncher who put the lie to this witticism was John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), who had the personality of a rock star. He was given to grand pronouncements, as when he wrote a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw, in 1935, predicting—correctly—that the book he was writing would “largely revolutionize the way people think about economic problems.”