TheoPol is on hiatus, as its author explores other projects.

Picture a world where politics is not so polarized. Imagine that the American people are flat out in favor of a plan that could lift more than a million of their neighbors out of poverty. And they’re arriving at this position not out of narrow self-interests—most Americans aren’t poor—but for essentially moral reasons. Actually, not much imagination is required. At least not when it comes to public opinion on a perennial issue: the minimum wage.

For decades, polling has shown support for a higher minimum wage ranging somewhere between unambiguous and unbelievable. In November, a Gallup survey found that 76 percent of the people would vote for a hypothetical national referendum lifting the bottom wage to $9 an hour. That’s $1.75 more than the current federal minimum; it would also be more than any increase ever passed by Congress. Last summer, a less independent poll conducted by Democratic-leaning Hart Research Associates found eight in ten Americans flocking behind a $10.10 per-hour minimum wage.

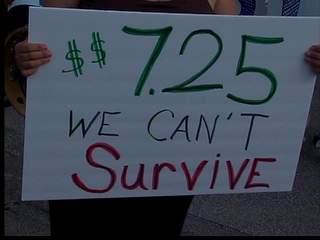

Try to identify a considerable subgroup of American opinion that’s content with the $7.25 regime. You’d think, for example, that self-identified Republicans would want to either freeze the wage or tamp it down. You would be mistaken, according to the Gallup breakdown: Republicans favored the $1.75 hike by an unmistakable 58-39 percent margin. Meanwhile, in a previous Gallup poll, the support among self-identified “moderates” was rather immoderate (75 percent).

Look at it from the other end. Those who want to hold down the minimum wage are a highly distinct opinion group in American politics. They’re of a size with the percentage of Americans who, according to other polling, are certain that aliens from outer space have visited the earth, and yet, they predominate on this issue, certainly at the national level. There hasn’t been a raise in the federal minimum wage since 2009, and few are betting heavily on the Fair Minimum Wage Act in the U.S. House of Representatives, which calls for a $10.10 minimum in three, 95-cent strides over the next three years. Just looking at the numbers, it’s as if UFO believers were dictating America’s air defense strategy.

Not that you have to be nuts to balk at a minimum wage.

Arriving at a dollars-and-cents figure will always involve a prudential judgment about how high the wage could go before it burdens hiring. And there’s plenty of room for debate over whether the legislated minimum should resemble a “living wage,” enough to adequately support a family. Even Msgr. John A. Ryan, the pioneering American Catholic progressive, did not go to that length in his classic 1906 study A Living Wage. Ryan envisioned a statutory minimum wage (unlegislated nationally until 32 years later) that would fall shy of a decent family-supporting income. Filling the gaps would be social insurance policies; prime examples today include Medicare and the Earned Income Tax Credit for low-wage workers.

But those are economic policy considerations. The politics of the minimum wage is a question of its own that begs attention.

Over the past few decades, public support for that policy has soared even as the value of the pay has sunk. By all accounts, if the minimum wage had merely kept pace with inflation since the late 1960s, it would be perched at well over $10 an hour today. What conclusions ought to be drawn from this thwarting of the public’s resolve? What does it say about the state of our democracy and the relations of power in our society?

A relatively benign conclusion might be that Americans aren’t particularly animated in their advocacy of a minimum-wage upgrade. In other words, the opponents may be a small choir drowning out the congregation, but that’s because the congregants aren’t trying hard to lift up their voices. That’s bound to be partly true in many policy debates including perhaps this one, but it’s equally true that those in the choir lofts of the U.S. economy have extraordinary means to project their voices, especially at a time when money is talking more loudly in politics than it has in almost a century. Lobbyists for trade groups such as National Restaurant Association and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce may have relatively few kindred spirits, on this question, but they’re heard above all in Congress.

A (Martin Luther) King’s Wage

The more likely conclusion is less benign: As wealth has consolidated into fewer hands, so has the power to overrule the public on bread-and-butter issues.

Those of us who subscribe to religious social teaching often speak of the need to nurture a moral consensus on matters affecting the common good. That laudable goal, however, is beside the point when it comes to the minimum wage (and some other issues of economic fairness, such as restoring the Clinton-era tax rates on the highest incomes). And that’s because we already have such a convergence.

The impulse behind the minimum-wage consensus is a moral one, in that it’s not rooted plainly in self-interests: boosting the bottom wage would give no direct lift to most Americans. They would seem to agree with Martin Luther King: “There is nothing but a lack of social vision to prevent us from paying an adequate wage to every American [worker] … ” But the political system today is unable to process this conviction. The minimum wage, adjusted for inflation, remains far lower than it was when King fell to the assassin’s bullet in 1968.

It’s clear that public sentiment in favor of a higher minimum wage is powerful. The problem seems to be that the American people aren’t. …read more