President Obama’s recent decision to send 100 armed military advisers to central Africa has turned a spotlight on the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel movement that crosses not only national borders but also the lines between savagery and spirituality. The advisers will be stationed primarily in Uganda and will not engage directly in battle with the guerrilla group, according to the Obama administration.

Though classified as a terrorist organization by the State Department, the LRA really isn’t a capital “T” terrorist operation like Al Qaeda with a clear and corrosive ideology. It’s more like a religious cult with a craving for crime and violence. The movement is a cross between the Sopranos and the sex cult Children of God, with the Manson Family tossed in for good measure.

Leading the force is the self-announced prophet Joseph Kony, who was raised a Roman Catholic. He began his career as a witch doctor and became the “spiritual adviser” to a previous incarnation of the LRA, a role that involved calling on the spirits to aid the rebels in battle. Not strikingly out of the ordinary for a fighting force in that region.

But something happened. As Todd Whitmore, a Notre Dame theology professor who has spent time in Uganda as a religious peacemaker, told me recently: “At some point he jumped the tracks. The people there say he went over to the dark side.” Kony launched the LRA more than two decades ago and began racking up his elaborate record of massacres, mutilations, abductions, and child sexual slavery.

Kony’s cult is a syncretistic mix of Christianity and traditional African tribal faiths. It roams the borderlands of murder and mysticism. Kony presides over cleansing rituals in which the soldiers, many of them children abducted by the LRA, are “purified” of their inhibitions against slaying the innocent. They are sent forth to do their deeds that also include rampant looting, which helps perpetuate the organization. Some observers, like Whitmore, believe the LRA is now a marauding criminal band as much as an anti-government insurgency.

Enter the Peacebuilders

Where are the bonafide spiritual leaders in this grisly picture? They’re right there, in the thick of it.

In a diary excerpted in a book compiled by Notre Dame’s Catholic Peacebuilding Network, Whitmore tells of a conversation he overheard among three Catholic priests in a northern Ugandan village a couple of years ago. Word had come that the LRA was surging toward the village. The priests hatched a plan to hop on their motorcycles and ride into the army’s onslaught, to give the villagers more time to flee. For unknown reasons, the attack didn’t materialize.

Whitmore also tells of going from hut to hut with “Sister Rose,” bathing and comforting people stricken by diseases and malnutrition as a result of warfare. His article, with the diary entries, is carried in the collection Peacebuilding: Catholic Theology, Ethics, and Praxis, published late last year by Orbis Books.

On a larger scale, the Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative has been working to transform conflicts since 1997. Bringing together Anglican, Catholic, Pentecostal, Seventh Day Adventist, Orthodox, and Muslim leaders, the interfaith group has dealt with land disputes and cross-border tensions, among other challenges. International faith-based agencies including Catholic Relief Services have stood with the local religious leaders, helping, for example, to reintegrate former LRA soldiers into the villages from where they came.

Some commentators have cast the LRA as yet another example of religious violence, which may be technically true but is barely descriptive. It’s clear who the real religious people are, in this unholy mess. They’re the ones forging what Whitmore describes as a “theology of presence” among the victims of war.

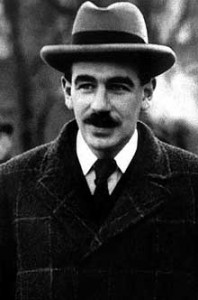

It has been said that economists are people who work with numbers but don’t have the personality to be accountants. One number-cruncher who put the lie to this witticism was John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), who had the personality of a rock star. He was given to grand pronouncements, as when he wrote a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw, in 1935, predicting—correctly—that the book he was writing would “largely revolutionize the way people think about economic problems.”

It has been said that economists are people who work with numbers but don’t have the personality to be accountants. One number-cruncher who put the lie to this witticism was John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), who had the personality of a rock star. He was given to grand pronouncements, as when he wrote a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw, in 1935, predicting—correctly—that the book he was writing would “largely revolutionize the way people think about economic problems.”