Celebrated as a civil rights milestone, the three marches in Selma, 50 years ago, also ushered in a new style of social and political advocacy. In the March 18 issue of The Christian Century, I write about what many of the marchers went on to do, after Selma, and the faith-based movement they made. (By the way, the Century has a website worth checking every single day.) Here is the Selma piece, in full:

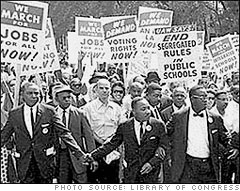

Fifty years ago, thousands marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. They were led by an eye-catching row of marchers, including a bearded rabbi, an unidentified nun in flowing habit, and Martin Luther King Jr. The third Selma-to-Montgomery march, which began on March 21, 1965, is rightly remembered as a watershed in the struggle for civil rights. Less known is how Selma refocused the lives of many, black and white, who gave the march its spiritual hue.

The trek to Montgomery began with more than 3,000 of the civil-rights faithful, whose ranks swelled by the thousands along the way. In that initial vanguard were several hundred clergy and untold numbers of lay religious activists from around the country. Voting rights became law five months later, just as many who had marched were letting loose their faith in a wider field of activism, taking on a host of social wrongs. They and others forged a new style of advocacy eventually known as the “prophetic style.”

Until the 1960s, white church people were easy to spot at a civil rights protest in the South, because they were scarce. Standing out among them was William Sloane Coffin, the 30-something Yale chaplain and a former CIA agent. In May 1961, Coffin made front-page news nationwide because he was white, well connected—and leading a group of Freedom Riders, who rode interracial buses across state lines to challenge segregated transportation in the Deep South. He emerged as the brash young face of incipient white solidarity with southern blacks.

In the next few years, religious involvement in civil rights—beyond black churches—gradually grew. In Selma, it was finally brought to scale.

On March 7, police brutally assaulted several hundred marchers, mostly young black men attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Known as “Bloody Sunday,” the event is dramatically and faithfully rendered in the movie Selma. In response, King issued an urgent plea for a “Ministers’ March” to Montgomery. Within a couple of days, an estimated 400 members of the clergy were wandering Selma, many of them having flown in with one-way tickets.

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, Jonathan Daniels had an epiphany during a recitation of the Magnificat prayer at the Episcopal Divinity School. The white seminarian dropped everything to go see the humble exalted in Alabama.

In New York, renowned Jewish scholar Abraham Joshua Heschel momentarily agonized over whether to travel on the Sabbath. Two years earlier, he had met King at a national conference on religion and race in Chicago, where the two became fast friends. “The Exodus began,” said Heschel at his opening address there, “but it is far from having been completed. In fact, it was easier for the children of Israel to cross the Red Sea than for a Negro to cross certain university campuses.”

Heschel was outspoken, but had never quite taken to the streets before. Two weeks after Bloody Sunday, there he was, marching with King in the front row.

After Selma, many intensified their activism and broadened their faith-and-justice lens. Jonathan Daniels stayed in Alabama, living with a black family, fighting in the trenches to register black voters, and earning a stay in county jail. In August 1965, at the age of 26, he was shot dead by a segregationist construction worker moonlighting as a sheriff’s deputy.

That summer, King turned his attention to the subtler humiliations of northern racism. Soon, he and his family were tenanting in Chicago as he shifted his focus from lunch counters and voting booths to knottier problems such as housing and employment. King was also trying to reason with new, harsh adversaries, ranging from white northerners to black militants who dismissed his inclusive, interracial vision of a “beloved community.”

Seven months after Selma, some of its alumni pivoted to a different cause altogether. They formed a national organization that came to be called Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam. Its leaders included Heschel, Coffin, radical Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan, and then-Lutheran pastor (later Catholic neoconservative) Richard John Neuhaus. The New York-based coalition spearheaded some of the first broadly based mobilizations against escalated warfare in Southeast Asia.

It was this group that brought King firmly into the antiwar fold, with his then-controversial “Beyond Vietnam” speech at Manhattan’s Riverside Church in April 1967. At the time, King called the war “an enemy of the poor,” linking the expense of intervention in Vietnam to the lagging War on Poverty at home. By the end of that year he was announcing the Poor People’s Campaign, an interracial effort for economic justice. It was King’s last crusade, a dream unfulfilled.

Through these struggles, King and others nurtured a style of politics rooted most deeply in the prophetic literature of the Hebrew Scriptures. It was a politics of vehemence and passion.

If this loosely bundled movement had a bible—other than the actual one—it was arguably Heschel’s 1962 book The Prophets. This study of the ancient radicals helped usher out the soothing spiritual happy talk lingering from the 1950s. Heschel wrote jarringly (and admiringly) that the biblical prophet is “strange, one-sided, an unbearable extremist.” Hypersensitive to social injustice, the prophet reminds us that “few are guilty, but all are responsible.” Heschel also explained that a prophet feels responsible for the moment, open to what each hour of unfolding history is revealing. “He is a person who knows what time it is,” the rabbi wrote, checking his watch.

The book caught on among spiritually minded civil rights workers. After perusing its pages, a young aide to King named James Bevel started going around in a knit skullcap, his way of paying homage to ancient Israel’s prophets. On the day of the final march in Selma, scores of other young, black, and presumably Christian men also chose to incongruously sport yarmulkes. Andrew Young, one of King’s top lieutenants, has recalled seeing marchers arrive with copies of The Prophets in hand.

After King’s assassination in 1968, Heschel and many other Selma veterans pressed forward (though not for long, in the case of Heschel, who died in late 1972). In 1968, Coffin became a household name as he stood trial for aiding and abetting draft evasion through his counseling of young men. So did Berrigan, who exceeded Coffin’s comfort zone by napalming draft records. In keeping up their prophetic ministries, they and others also spawned an assortment of imitators.

In the late 60s and early 70s, student antiwar radicals mimicked the so-called “prophetic style,” denouncing and confronting like the spiritual radicals but adding contempt and sometimes even violence to the mix. They designated themselves, in the words of counterculture leader Tom Hayden, a “prophetic minority.” Later on, from another ideological galaxy, came Jerry Falwell and the Moral Majority, which explored the boundaries between prophetic denunciation of perceived social evils and demonization of one’s opponents.

In these and other imitations, much of the prophetic spirit was lost—and the tone. King and likeminded clergy of the 1960s may have been quick to denounce and confront, but they scarcely if ever demonized or even denigrated. Typically they managed to blend strong moral convictions with degrees of civility and good will often unseen in politics today.

Issues that galvanized the 60s clergy still haunt us today. Racism, poverty, and war remain with us; even voting rights is a present-day cause, due most notably to the voter ID laws passed by a majority of states. The “Black Lives Matter” uprising against police violence has exposed racial chasms in many cities. Jails are increasingly packed with poor people who committed minor offenses or were unable to pay court-imposed costs. In 1968, King considered the level of the federal minimum wage to be beneath dignity; today, adjusted for inflation, it’s worth substantially less.

Such challenges invite a theological perspective—and a prophetic one. It’s not hard to find people acting on that impulse, people like Kim Bobo of Chicago-based Interfaith Worker Justice, who has crusaded against wage theft while invoking Nehemiah’s censure of plundering the poor. She and many others breathe life into a far-flung movement that hit stride 50 years ago on a bridge in Selma.