Last week, Ohio’s public employee unions were resurrected by the voters, who turned back a state law that had torpedoed collective bargaining rights for members of those unions. There and in many other states, public sector unions have been glaringly under pressure, so much so that it’s easy to forget about their counterparts in the private sector—which are faring much worse. More than a third of public employees in the United States are still unionized, but the figure in the private sector is now running, or limping, at barely seven percent. That marginal share is roughly equal to the percentage of Americans who identify themselves as Hindus, or who believe that Elvis is still alive, according to unrelated polling.

The seven-percent figure stands out for a different reason, in the mind of writer and historian Kimball Baker. It is identical to the percentage of private-sector workers who belonged to unions when a doughty group of men began their work in the early 1930s. These were the so-called labor priests—Catholic leaders who gave hope to downtrodden workers during the Great Depression.

“They played a big part in getting [the unionized segment] up to 35 percent in the 1950s and afterward,” Baker, a Presbyterian, told me recently, suggesting that it may be possible for pro-labor activists today to usher in another upsurge of unionism. That may be pure speculation on his part, but far more certain is the history he spotlights in Go to the Worker: America’s Labor Apostles—a history that is recurring now.

Priests with names like Hayes and Carey entered the work lives of a largely immigrant population, as Baker shows in his valuable book published last year by Marquette University Press. They walked with strikers on picket lines and opened “labor schools,” adult education programs in parishes, high schools and colleges that taught the nuts and bolts of collective bargaining as well as the highpoints of Catholic social teaching.

In the world according to the labor priests, taking part in unions and collective bargaining was not simply an exercise of individual rights. It was an act of solidarity, a way for workers to deepen their spiritual lives and give witness to the “mystical body of Christ,” a phrase that appears frequently in Baker’s profiles of leading labor “apostles” (including a few lay men and women from that era).

One of the below-radar trends in religion and politics over the past decade has been the decisive return of such labor “apostles.” Notably, few of them will be found in the Catholic hierarchy, which assembled in Baltimore this week with scarcely anything to say about such epoch challenges as income inequality. (See Francis X. Doyle’s November 14 op-ed piece in the Baltimore Sun titled “For U.S. bishops, economic justice isn’t on the agenda.”)

Like the old ones, the new labor disciples act locally. They preach in pulpits, rally seminarians, help organize low-wage workers, and sign up for pro-union campaigns (including the recent mobilizations on behalf of public employees in Ohio, Wisconsin, and other states). Unlike the old labor priests, the new activists are a diverse congregation. They draw from among Catholics, mainline Protestants, evangelicals, Jews, and Muslims, from the ranks of pastors, theologians, and people in the pews. The nerve center of the new religion-labor movement is Interfaith Worker Justice, a 15-year-old national organization based in Chicago with 70 spirited local affiliates nationwide.

The simple reason for this revival is that the debate over labor has returned to first principles: the right of unions to exist as a countervailing force in society. Many people of faith are choosing existence.

The Fall and Rise

In some pointed ways, religion and labor are a curious match. Christians, for example, sit for sermons about how the meek shall be blessed. Union members strike intimidating poses against workers who cross picket lines. But the two communities have overlapping social values, touching on the dignity of human beings and the work they do.

Religion and labor also have a history together. At times it has been a conflicted one.

The alliance of the past, symbolized by the Catholic labor schools, began to taper off in the 1950s, largely due to success. With the great industrial organizing campaigns behind them, there was simply less for religion and labor to do as a coalition. They went separate ways. Unions turned inward to build their institutions; religious activists gravitated toward new arenas of social action, notably civil rights and community organizing.

There was a tapering off but also a falling out. During the 1960s the Vietnam War was a harbinger of clashes to come, between mainstream labor’s hard-hat foreign policy and the anti-anti-communism of many liberal religious leaders. By the 1980s, churches and unions split further, over Central America.

The prospects of renewed friendship between religion and labor appeared with the passing of the Cold War. An early signal was the 1988-1989 Pittston Coal strike, which galvanized religious leaders nationwide, and which ended with the Virginia mining company withdrawing most of its draconian demands.

In 1996, Kim Bobo, a former anti-hunger activist who was raised a fundamentalist in Ohio, founded Interfaith Worker Justice with $5,000 left to her in her grandmother’s will. Owing largely to this growing network, the religion-labor movement today is arguably deeper and wider than it has ever been in the United States.

Though chiefly an activist organization, Interfaith Worker Justice has also helped renew theological conversations about human work and collective action, publishing a plethora of materials such as homily aids, liturgical resources, and papers and books. This is trickier than it may seem, in a religiously diverse movement.

But the group manages to occupy the common theological ground. “As God worked to create the world, our religious traditions value those who do the world’s work,” it says in a statement of purpose, adding—”We honor our Creator by seeking to assure that laborers, particularly low-wage workers, are able to live decent lives as a product of their labor.” It is left to be seen if any social alliance today will be able to bring about the conditions that do such honor to the divine. …read more

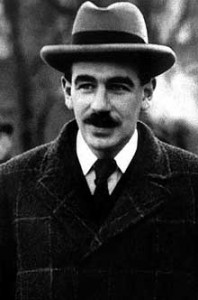

It has been said that economists are people who work with numbers but don’t have the personality to be accountants. One number-cruncher who put the lie to this witticism was John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), who had the personality of a rock star. He was given to grand pronouncements, as when he wrote a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw, in 1935, predicting—correctly—that the book he was writing would “largely revolutionize the way people think about economic problems.”

It has been said that economists are people who work with numbers but don’t have the personality to be accountants. One number-cruncher who put the lie to this witticism was John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), who had the personality of a rock star. He was given to grand pronouncements, as when he wrote a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw, in 1935, predicting—correctly—that the book he was writing would “largely revolutionize the way people think about economic problems.”