Over the past week, my thoughts about political matters have taken a sort of geographical turn, after going to see Father Gregory Boyle lecture at Boston College High School. The Jesuit priest is well known for his work with gang members in Los Angeles, far too many of whom he has buried over the years. Speaking to a lively overflow crowd in the school gym on a Tuesday night, Boyle did a remarkable riff on the Beatitudes, the eight “blessed are the … ” declarations by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount.

He noted that some translations of the sermon say “happy” instead of “blessed.” And, he pointed out that many biblical scholars are thrilled with neither word, because the more precise (if cumbersome) rendering of the passage from the Gospel of Matthew would be—“You’re in the right place.” That is: You’re in the right place if you’re merciful. You’re in the right place if you hunger and thirst for justice. And so on.

“It’s about social location. It’s about where we choose to stand,” said Boyle, who delivered the second annual Dowmel Lecture sponsored by the New England Province of the Society of Jesus on June 5. Then he offered this bracing interpretation—“The Beatitudes is not a spirituality. It’s a geography. It tells us where to stand.”

In the Lowly Places

Boyle takes his inspiration in part from Jesuit founder St. Ignatius Loyola, who instructed his recruits to “see Jesus standing in the lowly places.” He has inhabited such a place since the mid-1980s, when he arrived in East Los Angeles—often called the gang capital of the world—as a young pastor and quickly decided that presiding over funerals wasn’t going to be his signal contribution to gang members and their families. Two years later, in 1988, he started Homeboy Industries, a now-thriving collection of enterprises that include baking, silk-screening, tattoo-removal, landscaping, and other homie-staffed businesses.

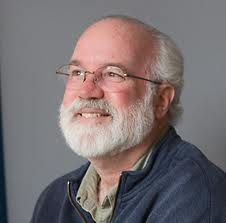

Boyle, a gentle soul who looked pleasantly rumpled in an old black blazer and an unpressed pale-blue shirt, recounted the Homeboy story with grace and wry humor. (The whole story is told beautifully in his book Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion, published in 2010 by Free Press).

In the beginning, he went looking for what he called “felony-friendly” employers who might want to hire the young ex-cons, and who were (not surprising to hear) few and far between. Then he got the idea to start some businesses—like Homeboy Plumbing, which didn’t exactly catch on. “Who knew? People didn’t want to have gang members in their homes,” Boyle said, tossing up his hands in mock amazement. “Who saw that coming?”

The Jesuit even made a joke with regard to the leukemia he has recently battled (and which is now in remission). He noted that he when he has an appointment at the hospital, he always gets a ride from a homie—which is “clearly more harrowing than the chemotherapy itself.”

Today, Homeboy Industries employs approximately 300 of those who used to run with gangs. One of its newer ventures, HomeGirl Café, staffed by female ex-gang members (“waitresses with attitude,” Boyle quips), serves about 2,000 customers a week at three sites. The broader organization also provides an array of social services such as tutoring and job training to more than 1,000 homeboys and homegirls each month. The vast bulk of them are on probation or parole.

What Boyle hopes for is hope itself. “Gangs are places kids go where they have encountered a life of misery,” he told the 500 or so lecture goers, among them students who read the Spanish-language edition of his book in a “Spanish Liberation Theology” class at the Jesuit high school, and who turned out wearing black-and-white Homeboy Industries T-shirts. “Nobody ever met a hopeful kid who joined a gang.”

Anyone with a Pulse?

During the Q&A, a young African American man asked the Jesuit if a white guy like him could really connect with these troubled young people of color. Boyle has a ruddy face and a bushy white beard—he could not be mistaken for a homie.

“Who can do this?” he asked rhetorically. “Anyone with a pulse. You can do it,” he said running a finger from one side of the audience to the other (over a crowd that included no slim share of Irish Catholic suburbanites). “If you’re receiving people and loving people, nobody will ever say, ‘You don’t understand.’ ”

The problems of the world are immense, and there will always be plenty of room for debate about the best solutions. But there is perhaps a simpler way of looking at the social challenges, the way of the Beatitudes. As Greg Boyle suggests, the clearest task of faith is not necessarily to take the right stands on issues, which are perpetually open to argument. The unmistakable task is to stand in the right places, with the lowly, despised, and afflicted.

Geography. …read more