The news from the nation’s capital this week was much about queues outside the Supreme Court, about the three days of oral arguments there over the Affordable Care Act, and most intensely, about the law’s so-called individual mandate—which calls for almost everyone to carry health insurance. The argument against the mandate is basically that it infringes upon a person’s rights, in this case, not to purchase a service he or she doesn’t want. If you missed the arguments over whether not having access to healthcare is an even greater violation of human rights, you could be forgiven. There was no such colloquy in the Court; there was scarcely a possibility of it.

The news from the nation’s capital this week was much about queues outside the Supreme Court, about the three days of oral arguments there over the Affordable Care Act, and most intensely, about the law’s so-called individual mandate—which calls for almost everyone to carry health insurance. The argument against the mandate is basically that it infringes upon a person’s rights, in this case, not to purchase a service he or she doesn’t want. If you missed the arguments over whether not having access to healthcare is an even greater violation of human rights, you could be forgiven. There was no such colloquy in the Court; there was scarcely a possibility of it.

That’s because we the people—or maybe just they the lawgivers and legal interpreters—have a somewhat pinched view of rights. We’re enamored of some rights but not others. As a nation we have a dynamic tradition of affirming (certainly in principle) negative rights—not to be harmed in some way. We have far less to say about positive rights, which uphold social and economic claims to a decent standard of living. These are the two great human-rights traditions, and we characteristically choose one.

Still, the unacknowledged rights are hardly just a matter of theory, even in the United States. They’re enshrined in international law as well as in religious and ethical systems of social thought.

For example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948, embraces the don’t-tread-on-me civil and political rights cherished by Western liberal democracies. But it also lifts up the social rights to food, housing, healthcare, and other goods—rights articulated by most Western democracies. And it constitutes part of international human-rights law.

The Universal Declaration is global though in no way alien to the United States. We not only signed it: We took the lead in drafting it. Its language and inspiration echoes in part the “Second Bill of Rights” proposed by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his 1944 State of the Union Address but never enacted, as Harvard law professor Mary Ann Glendon pointed out in her highly readable 2001 book A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Roosevelt called for economic rights including the guarantee of adequate medical care and a job with a living wage.

Support for social rights is the rule rather than the exception among the major religious faiths. The Catholic Church has probably the best-known system of social ethics, and the church holds emphatically that human beings have a legal right to the goods they need to participate actively in community. Marking the 50th anniversary of the Universal Declaration in 1998, Pope John Paul II spoke of social and economic rights as “inseparable” from other human rights.

John Paul went even further: “It is important to reject every attempt to deny these rights a true juridical status.”

A View from the Gurney

Personally I don’t go to the wall on the question of whether something like healthcare ought to be christened a right. It’s fine with me to call it a basic human need that any decent society should provide. Certainly, many thoughtful and conscientious people aren’t comfortable with the nomenclature of rights.

One of them is Edmund Pellegrino, an emeritus professor of medicine and medical ethics at Georgetown University who served from 2001 to 2009 as chairman of the President’s Council on Bioethics, a panel created by President George W. Bush. Pellegrino shies away from rights talk and prefers to speak instead of obligations, partly because, as he rightly observes, there’s no legal framework for economic rights in the United States. All the same, his critique poses a powerful challenge to the status quo on healthcare politics.

At an April 2008 forum on healthcare reform sponsored by Georgetown’s Woodstock Theological Center, Pellegrino (who is Catholic) shared a stage with a rabbi and an imam. All three stood by the fundamental moral precept that healthcare shouldn’t be treated as a commodity—as a business driven solely by market forces. Illustrating the difference between healthcare and other things that might be left to the marketplace, Pellegrino put it this way: “When you’re on that gurney, you’re not buying beer, panty-hose, or Band-Aids.” You don’t want market forces to determine the kind of care given to you. He continued:

Is there a moral obligation on the part of a good society to those who are sick, disabled, not able to function, and even to our brothers and sisters who are not taking care of themselves and are not being responsible, but who have the same dignity that you and I have?

That question, Pellegrino added, ought to be the starting point of any debate over healthcare policy. It barely surfaced this week in three days of considerations by the highest court in the land. …read more

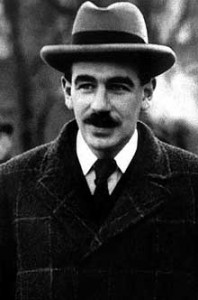

It has been said that economists are people who work with numbers but don’t have the personality to be accountants. One number-cruncher who put the lie to this witticism was John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), who had the personality of a rock star. He was given to grand pronouncements, as when he wrote a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw, in 1935, predicting—correctly—that the book he was writing would “largely revolutionize the way people think about economic problems.”

It has been said that economists are people who work with numbers but don’t have the personality to be accountants. One number-cruncher who put the lie to this witticism was John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), who had the personality of a rock star. He was given to grand pronouncements, as when he wrote a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw, in 1935, predicting—correctly—that the book he was writing would “largely revolutionize the way people think about economic problems.”