TheoPol is off its weekly schedule, running occasionally during the summer.

As I scan the headlines and hear the radio talk about the federal surveillance program, one thought keeps coming to me: Why don’t I give a poop about any of this?

Maybe it’s because I don’t understand the implications of collecting domestic telephone data. Or maybe it’s because I cling to the rustic notion of the common good, in which personal liberties are of course balanced with the needs of community. That would basically mean balancing my right not to be surveilled with our need not to be bombed.

There’s a chance I’d react differently if the NSA’s algorithms were to spit out a particular innocent person—me. And I guess there are real questions that need to be answered about the NSA program, questions framed well by the Times today. But I don’t feel that the government is necessarily trampling upon my liberty, by scanning for networks and patterns of telephone use. Google already knows more about me than I know about me.

And then there’s that quaint idea of the common good. What is it, anyway? Someone in the field of Catholic social ethics once said that defining the common good is like trying to nail Jell-O to a wall. But that hasn’t stopped theologians and church authorities from hammering away at it.

For instance, the Second Vatican Council defined the common good as “the sum of those conditions of social life which allow social groups and their individual members ready access to their own fulfillment.” There goes the gelatin, dribbling from the wall.

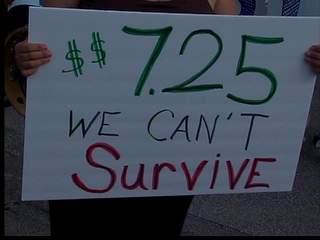

The Catechism of the Catholic Church tried to get more of a handle on the concept, by breaking it up into pieces. The Catechism cited three components of the common good: 1) “respect for the person” (including individual freedom and liberties); 2) “social well-being and development” (including rights to basic things like food and housing); and 3) peace—“that is, the stability and security of a just order,” the Catechism said.

It’s abstract, but I like it. The Catechism’s rendering makes it clear that this principle is about balancing, not choosing between, various personal and social goods.

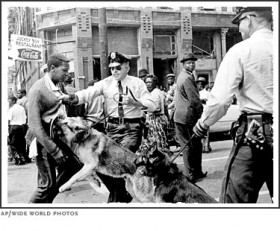

But I think the common good will always be subject to the Potter Stewart rule of knowing it when you see it. I see it in a raft of initiatives like gun control and progressive taxation, and yes, maybe even in Obama’s surveillance program. The critics of that program have real concerns about personal liberties, but these ought to be balanced with “social well-being” and “the stability and security of a just order.” The common good would seem to call for that. …read more