After Paul Ryan unveiled another one of his trademark balancing-the-budget-on-the-backs-of-the-poor plans, I found myself asking again, What’s the moral grounding for this fiscal sternness?

I raised that question in an item posted late last month. At the time I noted that while faith-based objections to draconian budget cuts are familiar enough, the moral and religious case in favor of such slashing is less clear. I promised to keep an eye out for real moral content in the arguments for balancing the government’s books.

In my search for such reasoning, I’ve scanned blogs, checked in on publications catering to fiscal conservatives, and broached the question with friends. I’ve also happily made the acquaintance of Jeff Polet, a scholar, writer, and not-so predictable conservative.

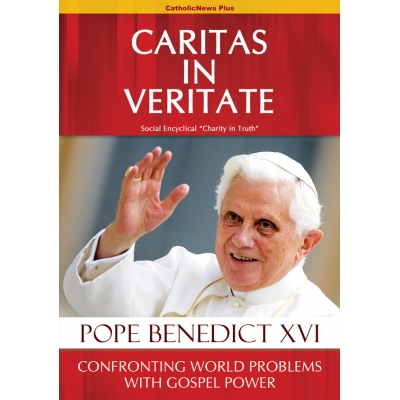

Polet is a political scientist at Hope College in Holland, Michigan, and a senior editor of the conservative online journal Front Porch Republic. He provided some evidence for the existence of moral and theological thinking in the deficit-hawk universe. For example, many liberals who speak on budget matters invoke values such as compassion and solidarity. Polet was just as quick to cite other legitimate virtues—temperance and prudence, among them.

“We’re spending money we don’t have,” he told me by phone in an interview I did for Our Sunday Visitor. “The bottom line is that we want a full range of services and we don’t want to pay for them.” He continued, “It’s a combination of greed, intemperance and a kind of luxuriousness. In an older time it would have been called decadence.”

When I asked him who the greedy are, he pointed to “interest groups” that oppose any cuts in programs that affect their constituencies, and fingered the AARP. I’d find it hard to pinpoint the elderly as a glaring source of national greed, not in these plutocratic times, anyway. But let’s stay on this trail.

As I noted previously, perhaps the only well-known moral claim on the fiscal right is a generational one—that we are saddling our children and their children with a crushing debt burden. Polet, a Catholic convert, roots the generational concern more deeply and evocatively in Scriptures. He pointed to the familiar biblical motif of inheritance (as in Genesis — “Abraham gave all he had to Isaac”).

“There’s this idea that parents owe their children an inheritance. You don’t take your inheritance and squander it, to the disadvantage of your own progeny,” said Polet, who chairs the political science department at Hope, an ecumenical Christian institution with Calvinist roots. “And that’s what I see us doing,” he added. “We’ve taken the cultural, financial inheritance we’ve been given, and we’ve squandered it in a lot of ways. So the world that we’re giving our children doesn’t seem to be as well-ordered as the world we inherited, certainly not from a financial viewpoint.”

I asked Polet if there might be another way of looking at the moral question of intergenerational solidarity. Do our obligations to the future extend only to the national debt? Or does the “well-ordered world” also need to include good schools, a solid infrastructure and a clean environment — which would require public investment now?

All that is part of a balanced way of looking at fiscal obligations, Polet acknowledged. “But if the debt problem gets too out of control, it’s going to make all those other things impossible,” he argued, falling back on a much-debated policy point (that our debt is unsustainable).

The Real Surprise

This will do, as a moral and religious case for fiscal hawkishness (and of course Polet has much more to say in his own writings). I didn’t come across much of that elsewhere—even among theocons, conservative religious types. I was unimpressed, for instance, by the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty’s “Principles for Budget Reform,” which barely even try to root policy assertions in moral or theological soil. The same goes for something called Christians for a Sustainable Economy, a largely evangelical ad hoc group that seems more ideological than biblical.

But Polet’s attention to moral and biblical foundations is not really what surprised me. I assumed that at some point I’d run into such thoughts among deficit foes. What I found intriguing were a few of his policy conclusions.

Here’s one: After arguing like many conservatives for scaling back Medicare, Polet added—“At this point, America would be better off going to a single-payer system.” The single payer, of course, would be the government, as national health insurer. He thinks this radical approach might be the only way to control healthcare costs in the future.

Needless to say, principled liberals have been making this particular case for quite some time. But I’ve never heard it from a conservative—maybe not even from a centrist. That gives me hope for a richer and less predictable dialogue on budgets and values. …read more