At the very least, the “right to work” is an impressive feat of branding, as demonstrated yesterday in Michigan. There, the ruling Republicans turned that heartland of industrial unionism into a right-to-work state—the 24th in the nation. Who isn’t literally in favor of such a right? The notion that a person shouldn’t have to pay union dues just to work taps deeply into the reservoir of American individualism.

And yet, ironies abound. I’ll name three:

First, proponents argue that right-to-work laws allow people to go it alone, if they so choose, without a union behind them. But the laws do no such thing. They allow workers to dispense with the obligations of unionism—i.e., paying dues for collective bargaining services. But workers retain the rights of unionism; they receive the benefits of such bargaining. The laws require that collective bargaining contracts cover all workers, both dues payers and free riders.

Second, right-to-work laws allow a minority of anti-union workers to opt out, when the majority has voted in a union. But they don’t allow a minority of pro-union workers to opt in, when the majority has voted down a union. A union can’t represent a minority of workers, according to federal or any state law. In other words, an individual worker is free to decide whether to join a union—as long as he or she decides not to. There goes the right to choose.

Third, the right-to-work people say government shouldn’t tell companies and workers what they can or can’t do. But the laws do exactly that. They make it illegal for a company to withhold union dues from paychecks, as part of a voluntary, negotiated agreement between free labor and free enterprise. Unions and employers together can’t set up a bargaining unit that includes every worker as a dues payer. That’s against the law in right-to-work states. So much for getting government off our backs.

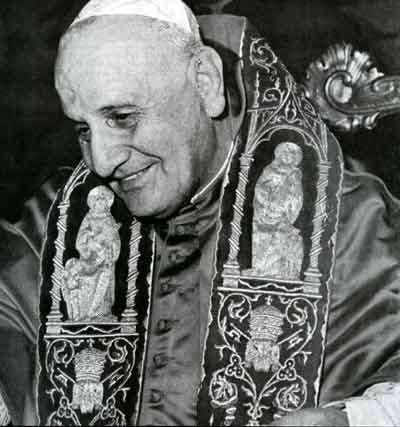

Twenty years ago, my friend and mentor in Catholic social teaching, the great and good Msgr. George G. Higgins, made the moral case for unions in his memoir, Organized Labor and the Church: Reflections of a “Labor Priest” (Paulist Press). Here’s a passage from that volume (on which I collaborated), dealing with right-to-work legislation and the common good:

In the argument over right-to-work laws, the first thing to get straight is that these laws have nothing to do with the right to work. That is, the very term is a verbal deception, a play on words to cloak the real purpose of the laws, which is to enforce further restrictions on union activity. Such laws do not provide jobs for workers; they merely prevent workers from building strong and stable unions…. Further, the pressure for such legislation did not arise from workers seeking their “rights.” The measures, rather, were uniformly backed by employers’ organizations and related groups, which continue to apply the pressure that keeps these laws on the books….

A favorite argument of the right-to-work lobby revolves around states’ rights. They argue that states should have the right to regulate labor problems according to their own desires, and that federal standards should not be imposed upon them. Frankly, the argument is less than honest. Under present conditions, the right to regulate labor unions has not been returned to the states. What is conceded [under the Taft-Hartley Act passed by Congress in 1947] is the limited power to enact union-security regulations more stringent than those in the federal law. But a state may not constitutionally enact regulations more favorable to the union movement.

After arguing a few other legal points, Higgins, who died in 2002, spoke to the moral question:

Apart from this, the argument about individual choice does raise serious questions. Even if an overwhelming majority of workers want a union shop, do they have a right to demand that the minority step into line with this decision? Since the right to work is the right to life itself, may conditions be imposed upon this right?

The answer to both questions, from my standpoint, is a straight yes. People are more than individuals; they are members of society. Such is their nature. For this reason, the rules necessary for harmonious social living may be binding, not merely optional. So, as members of civil society, we must obey laws, pay taxes, and fulfill our duties as citizens…. Likewise, the common good of industrial society may demand that individuals conform to rules laid down for the good of all.

Medical societies and bar associations generally have the right to lay down binding rules for their professions…. In business, few if any workers enjoy an unconditional “right to work.” The employer imposes rules concerning safety, performance of work, health and hygiene, and miscellaneous matters such as smoking and appearance…. These and other conditions of employment express the principle that the common good of the professional or plant community must prevail. In these matters, the right to impose conditions of employment is rarely questioned, even if the wisdom of particular conditions may be debatable.

Similarly, an employer and a union should have the right to agree, in collective bargaining, that union security—the requirement that workers assume some financial obligation to the union—would aid the industrial relationship. In agreeing to union security (when not prevented from doing so by right-to-work laws), the parties set out a norm of conduct for the common good of their industrial community. When a worker takes a job … he or she is no longer a detached individual; the worker becomes a member of the community and comes under its rules and norms. The alternative to such a system of ordered freedom is chaos and exaggerated individualism in the workplace.

I miss George Higgins. …read more