On an early spring day, students had filled a classroom at Boston College and were settling into light chatter when, a little after noon, English professor Elizabeth Graver came briskly into the room, accompanied by a svelte woman dressed in black and wearing a deep-red head wrap. Graver told the class that her guest—British novelist, essayist, and short story writer Zadie Smith—had just arrived from New York, where she is on the faculty of the creative writing program at New York University. Graver added unceremoniously, “Take it away, guys.”

Why Your Neighborhood is Still Segregated

Residential segregation by law ended gradually in America, notably with the 1968 Fair Housing Act; it took Congress another two decades to build enforcement mechanisms into the statute. But Richard Rothstein makes a sobering case that the damage was done—permanently. Today, Black families have barely one-tenth the wealth of their white counterparts. Rothstein says the vast divide is “entirely attributable to unconstitutional federal housing policy practiced in the mid-20th century.”

Rich Major, Poor Major

Researchers at Georgetown made news this week with listings of the college majors that lead to both the plumpest and leanest paychecks. Topping the plump list was petroleum engineering (yes, there’s a major for that), followed by such practicalities as pharmacy administration, computer science, and a slew of other engineering majors. The majors with the slenderest earnings included the performing arts but mostly occupations such as social work, human services, community action, early childhood education, and counseling psychology—in other words, professions defined by helping people.

None of this is surprising, and much of it could be chalked up to the way things are, this side of the Kingdom of God. Still, the Rich Major, Poor Major lists do raise questions about our colleges and universities. Are they simply training students to slot themselves into professional growth sectors like petroleum engineering? Or are they also finding ways to prepare young people for lives and careers of service to their communities and to their world?

Recently I had occasion to speak with undergraduate students who spent the past summer doing internships in the nonprofit and public sectors. These internships are almost invariably unpaid, and most of the students said they would not have been able to take them on, without special grants made available to them by their school—Boston College. They would have been unable to forgo the summer income and come up with the money for room and board in, and travel to, places ranging from Washington, D.C. and The Hague to the Dominican Republic.

“Men and Women for Others”

I say this not to give special kudos to BC (with which I’m associated). Its civic internship program is fairly limited and no more than what you’d expect from a Jesuit institution that speaks constantly of nurturing “men and women for others.” The point is that colleges and universities need to back up their rhetoric about service and the public interest with initiatives of this kind.

What follows is my account in the latest edition of Boston College Magazine, but first—a note about “men and women for others.” It has become a buzz phrase on Jesuit college campuses, and it’s heartening to simply hear a student speak those words, regardless of how he or she chooses to put them into practice. The slogan, though, has more of a theological and social edge than many of them would suspect. Here’s the original rendering, in 1973, by Pedro Arrupe, S.J., the beloved Superior General of the Society of Jesus:

Today our prime educational objective must be to form men-and-women-for-others; men and women who will live not for themselves but for God and his Christ—for the God-man who lived and died for all the world; men and women who cannot even conceive of love of God which does not include love for the least of their neighbors; men and women completely convinced that love of God which does not issue in justice for others is a farce.

And here’s the piece about the interns:

In late May, Samantha Koss ’14 began a 10-week internship at the U.S. embassy in The Hague, Netherlands, expecting to do research as assigned and otherwise assist embassy staff. She didn’t realize the embassy was shorthanded. And so, about once a week, she found herself walking or riding her bike to the Dutch foreign or defense ministry for a démarche (defined in the dictionary as a “diplomatic representation”). Accompanied by a career foreign service officer on each occasion, Koss would engage in discussion of a U.S. policy position with a Dutch counterpart. Details are classified, but she can say the meetings dealt with matters ranging from Iran’s nuclear program to the melting Arctic ice cap. Koss usually had several days to get up to speed on an issue before the démarche session. “It’s diplomacy, basically,” says the international relations major.

For Koss—who aspires to the diplomatic corps and plans to take the notoriously difficult Foreign Service Officer Test in October—it was her dream internship. Just weeks before she was to leave for The Hague, however, reality intruded. “I didn’t have the financial means to come out here and work for free. It wasn’t going to happen,” Koss recalled with a doleful shake of the head during a Skype interview in July. She spoke from the four-bedroom house (a minimalist cube-shaped structure owned by the State Department) that she shared rent-free with another female embassy intern. The Abilene, Texas, native did not start packing her bags until mid-May when Boston College’s Clough Center for the Study of Constitutional Democracy awarded her one of its 20 Civic Internship Grants for this year.

Founded in 2008, the Clough Center aims to provide undergraduate students with opportunities to acquire “the skills of civic engagement.” Over the past four summers, the center has presented stipends to 63 undergraduates for uncompensated work in municipal, state, and federal government offices (including the courts) and in nonprofit service agencies, both domestic and international. (A similar Clough Center program underwrites internships of Boston College Law School students.)

Vlad Perju, the center’s director and an associate professor of law, points out that student interns in public service fields rarely enjoy a paycheck. “It’s a big problem,” says Perju, noting that, for the many students who need to make and save money in the summer, full-time unpaid internships are “just not doable.” To qualify for a Clough award, a student must line up an internship before seeking the scholarship. Amounts have ranged from $900 to $4900, depending entirely on how long the internship runs.

“I didn’t have too strong a Plan B,” says Elizabeth Blesson ’15, an award recipient this summer. She adds that she probably would have returned to her job of the previous three summers, filing medical records at a Long Island, New York, hospital. The Lynch School of Education student went instead to the District of Columbia Public Schools headquarters. She helped coordinate job fairs for teachers laid off because of school closings, and she participated in a weekly seminar on education reform and school leadership offered to 80 summer interns.

A student’s academic record is a key factor in deciding on a Clough award. So is the nature of the internship, which has to in some way foster what the Clough Center mission statement describes as “thoughtful reflection” on the opportunities and demands of constitutional government.

A think tank qualifies. Damian Mencini ’14 worked with the Transnational Threats Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, an independent, nonpartisan research center in Washington, D.C. Using news sources such as Al Jazeera television and the English-language Libya Herald, Mencini, who is from Denver, helped to track the movements of jihadist groups in a region spanning central Asia to North Africa. “We call it the arc of instability,” says Mencini, whose research will figure in the project’s coming publications. Narintohn Luangrath ’14 spent her summer helping to track the worldwide movement of migrants and asylum seekers, at Georgetown University’s Institute for the Study of International Migration. She drafted background papers on the forced migrations that followed crises such as the 2011 Libyan uprising.

Highly partisan activities, such as political campaigning, do not qualify for Clough internship support, but a responsible position with an elected officeholder does. In Trenton, New Jersey, Christopher J. Grimaldi ’15 aided Governor Chris Christie “as a medium between the Christie administration and the media,” he said. The political science major’s chief task was to draft press releases for which he researched policy issues and dug through the Republican governor’s past speeches. Other Clough interns assisted Democratic legislators from New York, California, Massachusetts, Iowa, Connecticut, and Texas, working either in Washington or in district offices.

Six Clough students went to the State Department—all (except Koss) in Washington. In early June, military threats emanated from Egypt—and that caused Andrew Ireland ’14 to drop everything he was doing at the department’s Office of Conservation and Water. The threatened target was Ethiopia, now building a dam that Egyptian leaders say could hinder the flow of water through the Nile into their country. Ireland’s supervisor asked him for a quick background paper on a conference in Cairo at which politicians spoke incautiously of bombing Ethiopia or arming its rebels. Within a day, he prepared a three-and-a-half-page summary based on press items retrieved from an unclassified Central Intelligence Agency database.

On many other days, Ireland, a biology major and international studies minor, drafted memos on illegal trafficking of tusks, horns, and fangs extracted from endangered elephants, rhinos, and tigers, mostly in Africa. His research served as briefing material for higher-ups. “The assistant secretary of state is as high as I’ve seen it go,” he said, lifting a hand above his head in a July interview by Skype from his family home in nearby Bethesda, Maryland. He was speaking of Kerri-Ann Jones, head of the department’s Bureau of Oceans and International Environment and Scientific Affairs. Ireland and 20 staff members in his office met weekly with Jones.

Ecological concerns took Alexandra Moscovitz ’15 to the Dominican Republic, where she interned for the nongovernmental Caribbean Sustainability Institute. She had been there the previous summer and, with a local potter, created a gasification stove with an 18-inch-high, oval-shaped ceramic chamber. Gasification stoves run on crop waste (seeds, leaves, and other residue) rather than firewood that requires tree-cutting. “We weren’t able to find another ceramic gasification stove, so I think we made the first,” she says, explaining that ceramic is more durable than the metal often used in stoves of this kind. Returning this summer with assistance from the Clough Center, Moscovitz helped dozens of families swap out their inefficient conventional fuel stoves for her environmentally friendly ones.

Other Clough interns were Bridget Manning ’15 at Boston-based United Planet, which links young people to service opportunities abroad; Rebecca Kim ’15 at the Supply Education Group in New York, which is piloting low-cost private schools in developing-world slums; and Daniel Ryan Cosgrove ’16 at the Bucks County, Pennsylvania, district courthouse. In the fall, all will become Clough Center Junior Fellows, with the opportunity to attend Clough-sponsored forums, meet with guest lecturers, and participate in other activities that might include contributing to the Clough Undergraduate Journal of Constitutional Democracy, published each spring.

The expectation, says Perju, is that Clough Civic Interns will “bring their experiences back to the campus” and contribute to an environment of “thoughtful and informed discussion about public matters.” But, he adds, the ultimate purpose is to help nurture “the next generation of leaders in the civic sphere.” …read more

Sequestering the Moral Questions

On the eve of sequestration—the indiscriminate federal budget cuts—various interests are aiming to capture the moral high ground of the debate over government spending. Which raises the question: What exactly is the moral argument for slashing deficits and balancing budgets?

I’m very familiar with moral and religious appeals against budget cuts, particularly those affecting the poor. This week, for example, nearly 100 religious leaders issued a public appeal for Congress and the president to leave anti-poverty programs off the chopping block, declaring—“God calls for protection of poor and vulnerable people.”

Less clear is the moral case in favor of the meat ax. Yes, deficit hawks will deploy the language of moral responsibility, especially with regard to future generations that are allegedly endangered by government spending today. But these appeals are seldom grounded in moral and biblical principles such as solidarity, human dignity, and our collective obligations to “the least of these.” It’s mainly liberals (of a spiritual sort) who trade in such precepts.

On the right, perhaps the most identifiable moral claim is the generational one—that we are saddling our children and their children with a crushing debt burden. There’s room for debate about how unreasonable that burden will be, and whether fiscal austerity right now, in the midst of a still-undernourished economy, is a smart way to deal with the problem.

But there are larger questions about the generational argument. For example: Do our obligations to the future extend only to the national debt? Do our children also need good schools to get them started on their paths? Are we going to hand them a public infrastructure (roads, bridges, etc.) that isn’t crumbling all around them? And what about environmental protection—one of our most profound obligations to generations yet unborn?

All of that requires public investment now, and has to be balanced with the goal of easing the debt burden.

I’ll keep watch for moral content in the arguments for balancing the government’s books, and speak with some thoughtful fiscal conservatives on that score. I’ll report on those sightings and conversations before the next partisan crisis—which is due in late March, when the government runs out of money. …read more

Resembling Religion

In the continuing saga of the seculars in 21st century America, one question keeps occurring to me: Whose particular path might we be following, among the societies that have lessened their attachments to organized religion?

Are we going the gradual way of Western Europe, which began devolving religiously in the late 19th century and secularized slowly? Are we lurching toward Quebec, which went from being one of the more churchy regions of the Western world to one of the most anticlerical, in the space of little more than a decade (roughly the 1960s)? Or are we finding our own way in America, toward a religious future that’s hard to predict but will be exceptional in any case?

Another theoretical possibility is that the rise of the so-called “nones” is a passing fad. By way of his must-read Faith Matters blog, Bill Tammeus brings my attention to a commentary in the current Psychology Today that rejects this scenario. Titled “Why the secular movement is here to stay,” the article by attorney and secular activist David Niose offers several reasons, having to do partly with motive (a deep aversion to the politics of the religious right) and opportunity (secularists everywhere are now able to link up with each other through the Internet). Niose is president of the Secular Coalition for America, an anti-religious-right organization.

In other words, the seculars from this point on shall always be with us. “I think the author is right about that,” Tammeus argues, “but I don’t see any impending collapse of the number of Americans who say they believe in God (still above 90 percent in most polls) or who claim to be adherents of this or that religion.”

The award-winning religion writer continues:

In many ways—most good, some awful—religion is at the core of the American soul. Yes, its influence has waned and/or changed over time and some of that change has been for the better. (Tossing out prayer in public schools led by people whose salaries come from taxpayers is an example of a good change.)

But America is a landslide for religion, and it’s going to take a long, long time to undo that. My guess is that if it ever happens (doubtful) it won’t happen in the next several generations.

That said, it would behoove people of faith to listen to and learn from the secularists and to respect them as a legitimate subgroup of Americans.

I think Tammeus is right when he says Niose is right that the secular movement isn’t going away. And I don’t doubt religion is here to stay as well. But I’m not ready to predict that America will remain an overwhelmingly religious nation, for at least several generations and probably forever. There’s still the question of where we are, on the broad historical map of faith. Are we simply arriving late to the secular party, as England and Quebec did in the 1960s and ‘70s, following France, Holland, etc. Or will the turnout remain relatively small for that new social gathering space in the United States? Will religion keep a clear upper hand?

I don’t know. I don’t even know if those questions will be meaningful a decade from now. Maybe the lines between belief and unbelief, the secular and the religious, will be less stark than they seem today.

It’s possible that the seculars will eventually find a fairly ordinary place in the grand and vital scheme of (if you will) faith life in America. They’ll have their own communities, perhaps even denominations of sorts with differing perspectives on truth, ultimate reality, and the good life. They’ll have their own rituals. They’ll attend interfaith potluck suppers with the Hindus or Methodists down the street. They’ll come to resemble, not resent, religion.

Now that would be exceptional. …read more

The God Who Could Not

Last week, NPR’s Morning Edition presented a thoughtful, in-depth series titled “Losing Our Religion.” Reporters tracked down an interesting array of people who had turned away from organized religion, though not necessarily from spirituality and prayer. I was struck by how many of them had lost faith as a result of a personal tragedy, especially the death of a loved one. I was even more struck by an assumption they seemed to share with the most fervent religious believers.

The assumption is that any deity worth its salt must be omnipotent. God (if there is one) must be able to stop a deranged gunman from storming an elementary school in Connecticut, or catch a falling tree just in time to spare the lives of a young couple walking their dog in Brooklyn at the onset of Hurricane Sandy. But what happens if God could not?

One person who has agonized over this is Rabbi Irving Greenberg, former chair of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council. He has peered at the question continually through the horrific lens of the Shoah. “In the presence of burning children, how could one talk of a loving God? I once wrote that no theological statement should be made that would not be credible in the presence of burning children,” Greenberg said of its victims, in an interview adapted in The Life of Meaning, by Bob Abernethy (and me).

Greenberg recalled that as a young Orthodox rabbi, at times he could barely speak the words of the prayers recited daily by observant Jews. “It would be almost a mockery of the children to speak of the God who—as we do in our central prayer—redeems the children and saves them for the sake of his great name,” he explained. “How could you say that in a generation where there was no liberation?”

Between Belief and Unbelief

Greenberg’s message to those interviewed by NPR would be, to start with: I hear you. “Even for the most devout people, there are moments when the ashes of the smoke of Auschwitz choke off any contact with God or heaven. Therefore, I came to see that the line between the believer and the doubter is much thinner than I once thought,” he said (in what was originally an on-air interview conducted by Susan Grandis Goldstein for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly).

But he has kept his faith, partly with a fresh appraisal of covenant. In his interpretation of that biblical concept, God enters into a partnership with humans—and “self-limits,” as Greenberg puts it. God surrenders power, so that his/her Creation would have it.

Elie Wiesel … once suggested that the messiah, the all-powerful, deus ex machina God who saves us against our own will and ability—if that kind of messiah would come again now, it would be an outrage. It’s too late for such a messiah to come. It would have been a moral monster that could have come to save those children or to save those people and didn’t come.

But a God who wanted to intervene, and could not—that’s different, says Greenberg.

In a sense, to me, that’s the starkest, ultimate outcome. The fairy tale, the God of the white beard in heaven, all’s well with the world, the one who does it all for us, I think, is no longer credible, no longer possible. But a mature understanding of God who loves us in our freedom, who has called us to responsibility, who is with us at every moment—I think such a God is, if anything, more present and more close, and maybe, having suffered together and having shared our pain infinitely, is more beloved and maybe more inspiring to follow.

I don’t dismiss the perpetual question: If there’s an all-powerful God, how can such terrible things happen to the most innocent people? I just think the “if” could use some careful attention. …read more

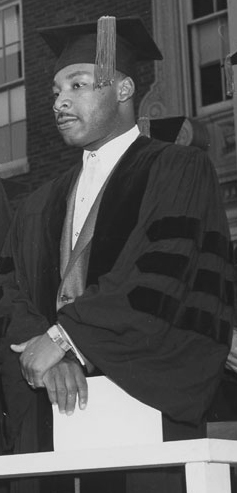

When MLK was Old

A new study published in Science magazine invites a fresh take on Bob Dylan’s refrain, “Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.” The study of 19,000 adults found that most people realize how much they’ve changed in the past ten years but seriously underestimate how different they’ll be in the future. People of all ages think they’ll stay pretty much the same—incorrectly, according to the Harvard and University of Virginia researchers. They call it the “end of history illusion.”

That’s to say, we think we’re so much older and wiser, but we’re younger than that now. There’s more growth to experience—different values, preferences, and personality traits to make our own. I don’t know if that’s necessarily comforting. Depends on how much you want to stay “just the way you are” (with apologies to Billy Joel). There were helpful summaries of the study and its methodology in Science Times and the Boston Globe, and at NPR online.

With Martin Luther King Day coming up, it’s worth asking how many of history’s great figures would have predicted how different they’d be, ten years out. I don’t think MLK, sprinting to his doctorate in theology at Boston University in 1953, had a clue.

Absorbed in Hegel, Tillich, Niebuhr, and others, King had what he saw as a clear picture of his future self. It involved standing at the front of a class in social ethics at a seminary or university, preferably a northern institution. As Stephen B. Oates recounted in his 1982 biography of King:

He hadn’t all the answers, by any means. He realized how much more he had to learn. But how he enjoyed intellectual inquiry. He would love to do this for the rest of his life, to become a scholar of personalism [the philosophical school that engaged his mind at B.U.], the Social Gospel, and Hegelian idealism, inspiring young people as his own mentors had inspired him. Yes, that would be a splendid and meaningful way to serve God and humanity.

King—on track to become a tweedy tenured theology professor—was so much older then.

A year later, he accepted what he assumed would be a sleepy temporary pastorate in Montgomery, Alabama. Newly married to Coretta, he took the job at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, a relatively affluent congregation, figuring he’d get a little pastoral experience and draw a paycheck while wrapping up his doctoral dissertation.

Coretta wanted to get out of the Deep South as soon as possible. But on December 1, 1955, a 42-year-old seamstress named Rosa Parks refused to surrender her seat on a city bus to a white passenger, and was escorted to the police station. Uproar ensued, and King’s fellow clergy, a fairly timid bunch, drafted the 26-year-old into the leadership of what became the Montgomery Bus Boycott. There was no turning back.

Postscript

Last week, the Bible that MLK used in his early ministry made news. It was announced that Barack Obama would take the oath of office with his hand on King’s Bible as well as Lincoln’s. That’ll come at the highpoint of the January 21 inauguration ceremony, which happens to fall on the King holiday.

On the inaugural platform, you won’t have to look far to find a living person whose identity changed in unexpected ways. Just keep an eye out for Barry Obama. …read more

Read Thy Enemy

I flipped through some of the expected commentary about what to read in the New Year, but one column that nudged me was Ross Douthat’s in the Times, “How to Read in 2013.” The conservative pundit issued a moderate challenge: “Consider taking out a subscription to a magazine whose politics you don’t share.” He made a point of using what he referred to as that fusty word, “subscription.” Reading all of a magazine, Douthat explained, is a better way of grappling with its ideas than plucking this or that item from its web site.

So, if you wait for National Review to arrive in your mailbox, or inbox, make sure you also get The Nation or The New Republic, Douthat suggested. Or, if The New Yorker is your blend of tea, think about subscribing also to The Weekly Standard.

“And don’t be afraid to lend an ear to voices that seem monomaniacal or self-marginalizing, offensive or extreme,” he advised. “There are plenty of writers on the Internet who are too naïve or radical or bigoted to entrust with any kind of power, but who nonetheless might offer an insight that you wouldn’t find in the more respectable quarters of the press.”

The December 29 column has led me to take stock of my own reading. Like most members of our species, I am attracted to ideas and information that confirm my positions and worldview. There are names for that in the social sciences literature—“confirmation bias” and “pattern bias” come to mind.

Although I prefer the left-leaning MSNBC, I do go to the conservative channels. But for me, watching The O’Reilly Factor or some other Fox News productions is like eating a vegetable I don’t care much for—without the consolation that it’s good for me. I find more appetizing the (online) offerings of National Review and especially The American Conservative but tend to pick and choose among them. I usually pass up the antigovernment and free-market screeds. More palatable to me are pieces that tap into my culturally conservative sentiments, which I wear less on my sleeve than I used to.

Taking up the Douthat challenge, I’m not sure if I’ll actually take out a new subscription to a politically conservative journal this year (or a liberal one, for that matter). But I’ll add to my New Year’s resolutions an intention to regularly sit down in the periodical room of a Boston College library and read The Weekly Standard or The American Spectator cover to cover.

At the same time, I’ll make an effort to read books and articles outside the political-theological-philosophical complex. I’m already starting to crowd out that resolution, though, with items piling in my Amazon cart. I’m eagerly awaiting the February release of Jeffrey Frank’s Ike and Dick: Portrait of a Strange Political Marriage, about Eisenhower and Nixon.

Douthat’s column has evidently touched a chord with many readers, and I’m glad for that. But is he putting his finger on the most glaring oversight in our politics today? Would that be the failure of liberals to read conservatives and vice versa? Or would it be that too few people in general are listening to the least of these, to the weak and vulnerable?

At one time—prior to Michael Harrington’s 1962 classic The Other America—the poor were invisible. Now they are simply inaudible. They’re seen waiting at bus stops and standing behind fast food counters, but seldom heard in our public debates. And I wouldn’t expect to hear their voices all that clearly in the pages of The Weekly Standard. But maybe I’ll be surprised. …read more

A Word About the Weather

Even TheoPol is not quite prepared to say that theological and moral perspectives are especially critical to discussions of climate change. One would think facts and science—the inconvenient truths, as far as we know them—should be uppermost in the public debate. But theology has a way of crashing parties, including the political ones.

For now, I’ll say there’s an important link between theological ethics and at least one aspect of global climate change: relationships between rich and poor nations. In their 2001 pastoral letter, Global Climate Change: A Plea for Dialogue, Prudence, and the Common Good, the U.S. bishops zeroed in on four points about equity in these relationships.

1) Rich and poor nations alike have a responsibility to address the climate threat;

2) Historically the advanced economies have generated the highest levels of greenhouse gas emissions known to cause climate disruptions;

3) In addition, wealthy nations have a greater capacity to lessen the threat of climate change, while many impoverished nations “live in degrading and desperate situations” that lead them to adopt ecologically harmful practices;

4) Advanced economies should bear the heaviest responsibilities for solutions to climate change. “Developing countries have a right to economic development that can help lift people out of dire poverty,” the bishops noted. “Wealthier industrialized nations have the resources, know-how, and entrepreneurship to produce more efficient cars and cleaner industries,” and they should “share these emerging technologies with the less-developed countries….”

These too are inconvenient truths. Undergirding them are moral and theological principles, among them solidarity and the biblical “preferential option for the poor.” Of course, all this is tendentious drivel if you think global warming is a hoax. Which brings us back to science—until further word. …read more