I’m not naturally a fan of looking at life through the lens of business and management. I’m inclined to do the opposite and see business in the light of other things, like faith and values. I’m not enthused by arguments that government should run like a business, that strong families are like corporate teams, or that students are the “customers” of colleges and universities. Something vital gets lost in the translations.

On the other hand, if St. Ignatius Loyola was right—that God and truth can be found “in all things“—then that has to include business. And I’ve taken a growing interest in management thinking on some valuable questions such as how we change and where ideas come from. (That’s aside from the journalistic fun of turning dissimilar phrases on each other, although one has to be careful when milking sacred cash cows.)

In that spirit, I offer here a piece that ran on Tuesday in Forbes online, “What a CEO Can Teach a Pope,” coauthored by Andy Boynton, a friend and dean of Boston College’s Carroll School of Management, and me. The item was this month’s installment of Boynton’s monthly Forbes blog, “Leading with Ideas” (on which I collaborate).

In the days leading up to the election of Pope Francis, Thomas J. Reese, a noted Jesuit priest and scholar at Georgetown University, was widely quoted as saying that the next successor to Saint Peter needs to be “Jesus Christ with an M.B.A.” That’s a colorful way of putting it, and probably not many Roman Catholics would want a Vicar of Christ to talk like a VP of Strategy. It would be more than curious to hear a papal address about the church’s “core competency” or its need to “ideate” and achieve “synergy.”

Still, Reese’s point is well taken. For one thing, many observers say Francis will have to manage the seemingly unmanageable Roman curia, the Catholic Church’s governing body that has served up such media sideshows recently as the case of “the pope’s butler,” who leaked secret Vatican documents, and a corruption scandal at the Vatican bank. But that’s only for starters.

Let’s look at this for a moment the way a CEO would.

These days the marketplace of belief and unbelief is highly competitive. Religious sects, including Pentecostals and indigenous faiths, are proliferating in places like Africa and Latin America. Other movements—notably, the “spiritual but not religious” phenomenon—are also gaining traction, especially among young adults, including many nominal Catholics. There are growing numbers of “nones,” people who check off “none of the above” when polled on religious affiliation. A pope, one could say, has to come up with ways of bolstering the church’s share of this dynamic market.

Any multinational organization, let alone one with more than a billion customers, has to figure out how to adapt and innovate. But that’s not what the Catholic Church and many other big institutions are good at. The church does many things well—teaching and reaching out to the poor, to name a couple. Timely innovation is not one of them.

Borrowing a page from an illustrious manager, Catholic leaders might do well to consider that ideas for improving the church are everywhere—not just at meetings of bishops or other likely places. Such was the spirit that Jack Welch brought to American business, particularly to General Electric, in the 1980s. Until then, corporate America shared an animus against any idea or product “not invented here,” placing an exclusive priority on the creation of novel ideas within the boundaries of an organization. People were rewarded with bonuses to the extent that they conjured up such notions.

Welch arrived on the scene and set out a new vision. He originally called it “integrated diversity,” but the approach came to be known, more felicitously, as “boundarylessness.” One result was that GE went looking for ideas in the wide corporate world—”Someone, somewhere has a better idea,” he said—and happily adapted these ideas to its specific needs. As Welch once commented in a documentary, “It’s a badge of honor to have found from Motorola a quality program, from HP a product development program, from Toyota an asset management system.”

Likewise, a Catholic bishop might consider it a badge of honor to get an idea about religious education from the North American Jewish Day School Conference, or an insight into the broader culture from a novel written by an atheist. The Catholic Church has always absorbed such influences to some degree, which is how it has transplanted itself into so many cultural contexts over the past two millennia. But keen observers also note that when it comes to making important decisions, the church, like many other organizations, succumbs to the “Not Invented Here” syndrome. Ideas come mainly from within, from top management, and that’s not good.

2,000 Years of Steady Growth

Needless to say, corporations can also learn from the Catholic Church and religious orders such as the Jesuits—about mission, values, and global perspective. But the church does need fresh ideas, and if it’s looking high and low for them, it might as well listen to what concerned people in business management, or recently out of that world, are saying. One of them is Father Tom Doyle, who, in his preordained life, was a consultant with Deloitte & Touche.

To start with, Doyle points out that the church hasn’t exactly been a slow grower, when you take the long view. It began with 12 members—Jesus’ apostles—and now has 1.2 billion adherents around the world. “That’s almost 2,000 years of an annual growth rate of 1 percent,” he told Caitlin Kenney of NPR’s All Things Considered recently, on a light note. “That’s pretty long and pretty incredible growth.”

At the same time, Doyle and others believe the church needs to begin thinking more strategically about its brand, which has suffered in recent years, at least partly because of the sexual abuse scandals. The solution they’re recommending is greater transparency on the part of the institution that emerged last week from the secret conclave.

“This was a huge frustration for all our consultants: a lack of transparency can hurt your brand,” Kenney reported, speaking of Catholic managers and consultants interviewed for her March 6 report. “It can drive away your customers. And as the Catholic Church has recently discovered, this lack of transparency could have much darker implications.” Pointing to the scandals and an erosion of confidence in the church, Kenney added, “People stop trusting that the Catholic Church would tell them the truth.”

For his part, Doyle said he gives the same advice to the church as he would to any company in crisis. “How do you get trust back? You earn it. You have to earn it, right? And so we’re going to have to err on the side of being more transparent about things than we have in the past.”

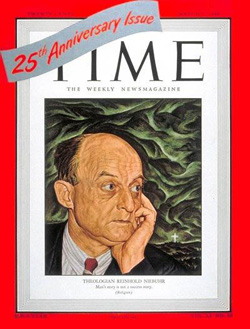

Most of all, the church and every big institution would do well to put on its listening ears. Listening to various stakeholders—customers, people all levels of the organization, and others—has become a critical part of strategies for designing products and processes in many (though not enough) companies. And the innovation would go a long way in the Catholic Church as well. In its March 18 issue, the Jesuit magazine America editorialized that the church needs to do a better job listening specifically to five groups: the poor, victims of sexual abuse, women, gays and lesbians, and theologians (with whom the hierarchy has an often-frosty relationship).

Listening—in a large and complex organization—is a lot harder than people think. The church may need to get some help with that, perhaps from sympathetic consultants who could facilitate the conversations with different stakeholders. But the good news is that you probably don’t have to be “Jesus Christ with an M.B.A.” to start the ball rolling. …read more